Every number is a life: The child poverty crisis in stats

Millions of children in the UK are going without basic essentials – how we count them matters. Claire Miller drills into the numbers behind child poverty.

Child poverty is at a record high. That means millions of children surviving on food bank visits and missing out on parts of childhood many take for granted. But how did we get here? And what do we do about it?

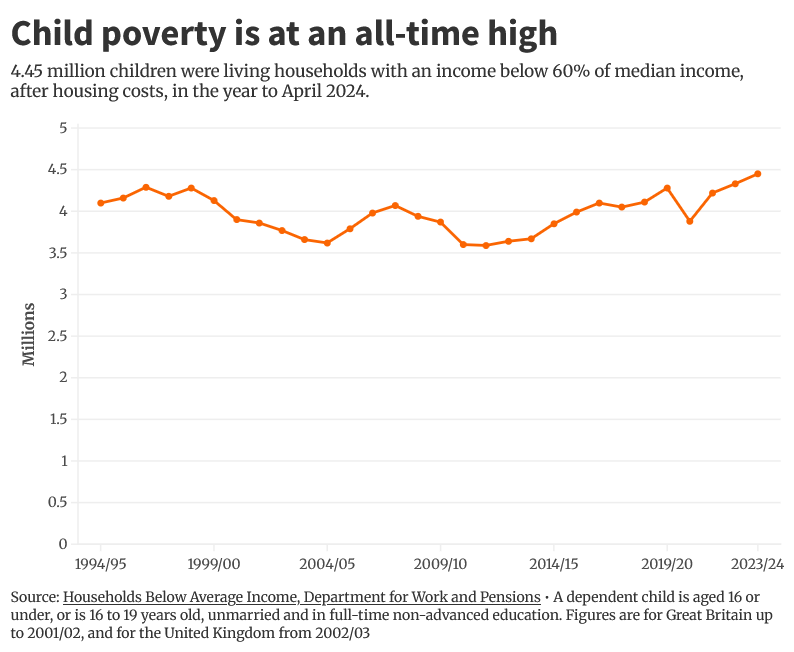

In the year to April 2024, 4.45 million children were living in poverty, according to the Government’s headline measure. That’s 31 per cent of children. Or, if you had a class of 30, nine of those children would live in low income households.

There isn’t just one way to count children in poverty.

This is why you can get a government claiming credit for a fall in one measure, while being criticised by the opposition for a rise in a different figure. So, what is the truth of the scale of this crisis? Who exactly is being counted to get to 4.45 million children in poverty?

Children are in poverty if their household’s disposable income – after housing costs – is below 60 per cent of median income. This is relative poverty; people who have a low income compared to the average.

Children include those aged under 16, as well as those aged 16-19 in full-time education, but not at university.

Disposable household income is income from wages, benefits and pensions after tax, rather than what people have left over after paying for all the essentials. Poverty levels can be measured before or after taking off housing costs (rent, mortgage interest and water bills). The median income is the point in the middle if you line up everyone’s household income from smallest to largest.

We also measure absolute poverty levels, where disposable household income is below 60 per cent of the median income in the year to April 2011, adjusted for inflation. Absolute poverty reflects whether incomes are keeping up with inflation.

What do the numbers really mean?

Less money might mean not enough food and poorer health. It might mean missing out on essentials and a disrupted education. The data we use to calculate poverty rates also tells us more about life on a low income.

One in 13 children across the UK (8 per cent) live in a household that needed a food bank in the previous year, up from 6 per cent a year before. For children classed as living in poverty, that rises to one in six.

Nearly a fifth of children (18 per cent) live in homes where they are at risk of, or already are, not getting enough food, particularly good quality and varied food. For children living in poverty, it’s a third. This is the worst it’s been since this measure was introduced in 2019/20.

Food insecurity has knock-on effects. A survey of paediatricians by the charity Child Poverty Action Group [CPAG] found 99 per cent reported poverty contributing to ill-health among the children they treat, with many raising concerns about children’s nutrition.

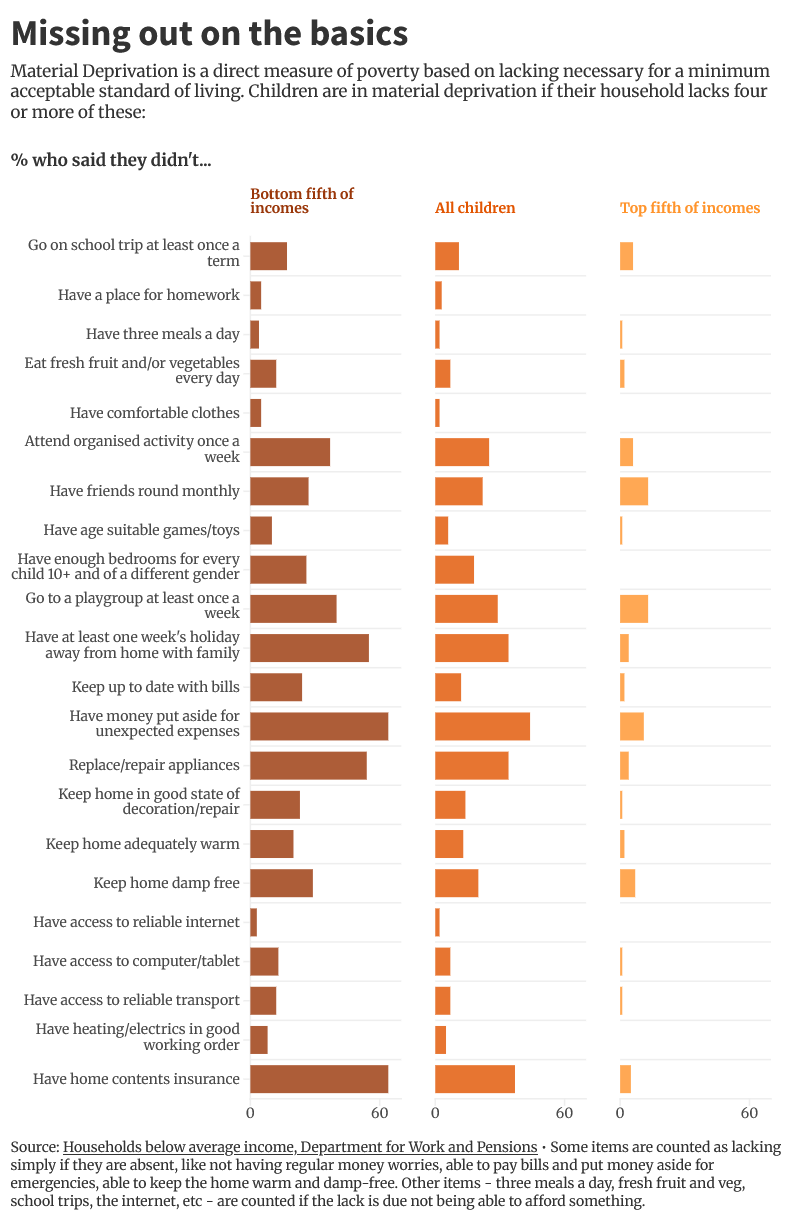

Low incomes mean families struggling to afford everything, not just food.

In the year to April 2024, 4 million children were in material deprivation in the UK, which was 28 per cent of all children. This means they may live in households that struggle to pay bills or can’t afford to keep homes warm and damp-free. They may miss out on toys, school trips, hobbies and having friends over.

Research by CPAG found 16 per cent of 11–18-year-olds had missed school at least once because they didn’t have something they needed to attend, rising 26 per cent among those who qualify for free school meals.

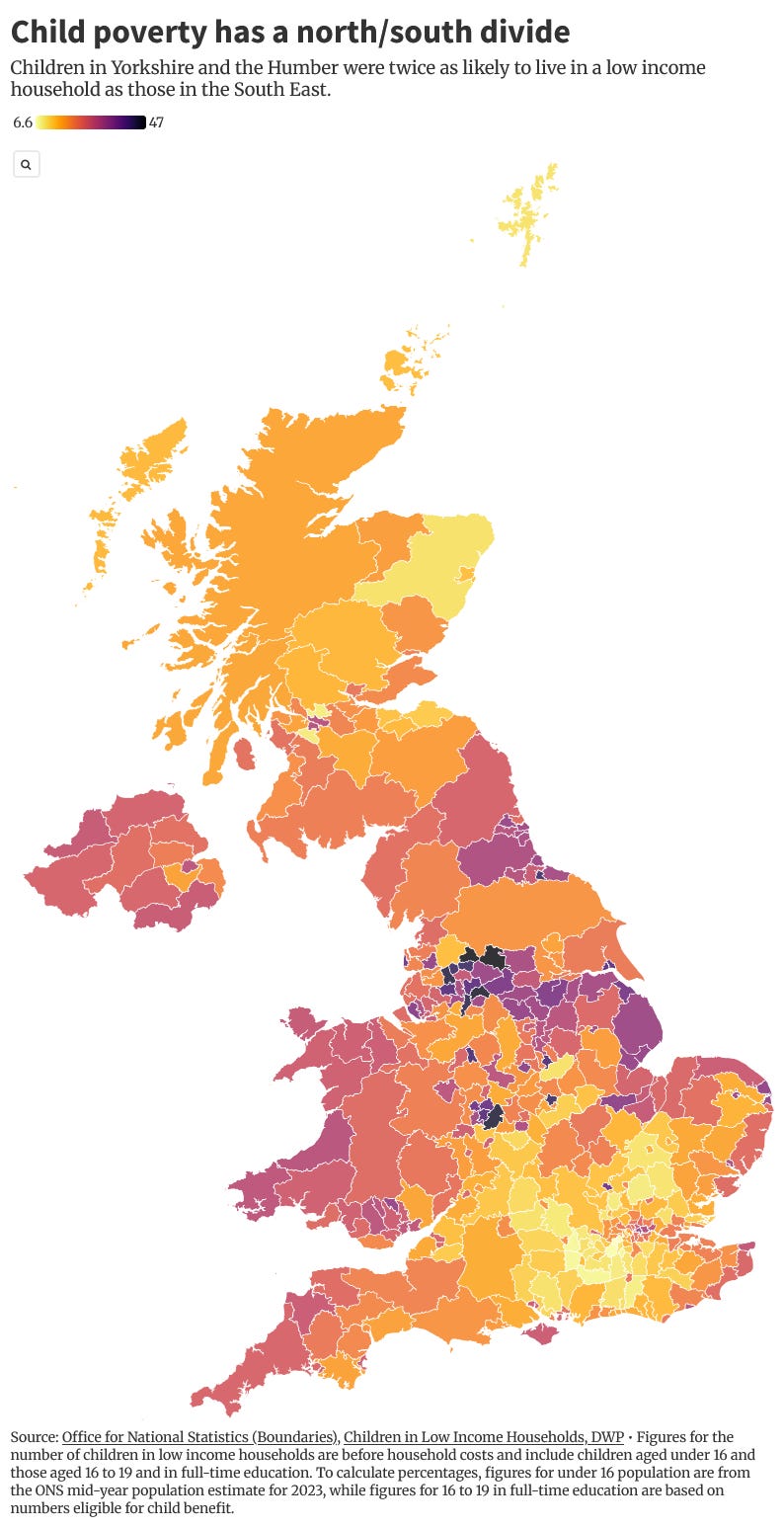

A national problem

Child poverty isn’t evenly distributed across the country. Children in the hardest hit local authority area are seven times more likely to live in poverty compared to those in the area with the lowest rates.

Nearly half of children in Pendle (47 per cent) are in poverty before housing costs. In Richmond Upon Thames, it’s just 7 per cent.

Unhelpfully, unlike earlier figures, these are measured before housing costs. After housing costs figures would likely be even higher, especially in London where rents and house prices are highest.

Yorkshire and the Humber has the highest poverty rates in these figures at 32 per cent, followed by the West Midlands (31 per cent) and the North East (30 per cent). The lowest rates are in the South East (16 per cent), Scotland (18 per cent), and the East of England (19 per cent).

Why are so many children living in poverty?

Children are more likely to live in low-income households (31 per cent). That compares to 19 per cent of working age adults, 16 per cent of pensioners, and 23 per cent of households where someone is disabled.

Child poverty is also more persistent. A fifth of children (18 per cent) were in low income households in at least three out of the four years to 2023. That compared to 11 per cent of both working-age adults and pensioners.

Broadly, parents tend to earn less when their children are young compared with adults in households without children, larger households need to make incomes go further, and their housing costs tend to be higher as they need more space.

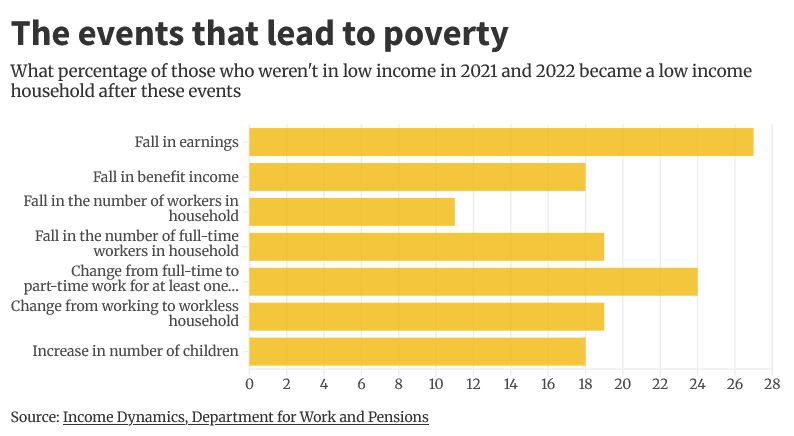

Families where no-one works are most likely to be in poverty (65 per cent). But working fewer hours and/or for lower pay also means higher poverty rates. Caring responsibilities, low levels of qualifications, and family size can make earning more hard.

A fall in earnings is the event most likely to put household incomes below the poverty line. But nearly a fifth of families (18 per cent) tip into poverty after the arrival of a new child. Knock-on impacts like someone giving up work for childcare add to the risk.

Why are numbers rising?

Working parents became poorer. With relative poverty, how everyone else is doing matters.

Earnings for households with children fell between 2023 and 2024. While children in households where all the adults work are less likely to be in poverty, at 17 per cent, this was up from 14 per cent the previous year. Poverty levels fell for families where some but not all adults work and for workless families.

Slow wage growth meant these households really felt the end of cost of living support schemes such as the Energy Bills Support Scheme and the council tax rebate.

Some cost of living support continued for those on benefits and pensions. And a 10.1 per cent rise in most benefits and the State Pension covered some of the losses from general schemes ending.

But because of the two-child limit and the benefit cap, families were less likely to see the benefit of those rises.

How do we tackle child poverty?

To have any chance of stopping child poverty rising further, pretty much everyone – charities, think-tanks, Labour deputy leadership hopefuls – agrees the two-child benefit limit needs to go.

The two-child limit restricts support in Universal Credit to two children in a family, if they had a third or subsequent child born on or after April 6, 2017.

Children living in households with three or more children now make up half (48 per cent) of those living in poverty, up from 37 per cent the year before the policy was introduced. Research by the Resolution Foundation has found that, on current policies, the child poverty rate is projected to rise from 31 per cent in 2023–24 to 34 per cent by 2029–30 – equivalent to 4.8 million children. It estimates that abolishing the two-child limit would prevent this increase and help maintain the child poverty rate at around 31 per cent by the end of the decade.

Senior Labour figures have reiterated that tackling child poverty will be a core test of fairness and economic success for the next government. The party has pledged to review the two-child limit and wider welfare system as part of a comprehensive anti-poverty strategy, alongside new measures to support families with the cost of living.

But reversing the rise in child poverty will require a broader set of actions – both immediate and long-term – including ensuring child benefit and Universal Credit rise in line with inflation, expanding free school meals to more families in need, and boosting support for childcare and early years services. In the longer term, it will involve improving welfare safety nets and investing in affordable housing.

The Government’s child poverty strategy is set to be published imminently. With its recommended actions, and November’s Budget, could come decisions that impact how many children will grow up with too little over the coming years.

About the author: Claire Miller is a freelance journalist who specialises in using data and the Freedom of Information Act in her reporting.

Here at The Lead, we’re campaigning to end child poverty. We have already reported on the crisis as a failure of the state, and the under-reported racial inequalities lying at the heart of child poverty. If this is an issue you care about, share this article to raise awareness and help more people discover our journalism.

Subscribe to The Lead today and get a 30% discount on annual membership – only available until the end of November.