The Lead Untangles: Election campaigning laws

Whether Reform have been breaking them – and what to do if you suspect foul play.

The Lead Untangles is delivered via email every week by The Lead and focuses on a different complex, divisive issue with each edition. The entirety of The Lead Untangles will always be free for all subscribers.

Get beyond the headlines and make sense of the world with The Lead Untangles direct to your inbox. And support us to get into the people, places and policies affecting the UK right now by becoming a subscriber.

The Facts

Last week, Reform was accused of breaching electoral law after letters sent to residents in Gorton and Denton did not include an imprint explaining they were from the party – which is illegal.

Reform UK had commissioned, printed and sent the letter from a local pensioner, and printed it in faux-handwritten text, a campaign tactic also used by the party in Caerphilly. However, it was not made clear that the letter in Gorton and Denton, where Matt Goodwin is Reform’s candidate in the upcoming by-election, was campaign material, leading to a police investigation. A few days after the Manchester Mill reported on the incident, the printing company used by Reform UK (Hardings Print Solutions Limited) took the blame and said sorry.

But this isn’t a standalone issue. Merseyside Police investigated a Reform candidate from Wirral West in 2024 after he sent out leaflets that did not contain the required imprint.

It also appears Matt Goodwin has not included a digital imprint on his campaign videos online (although he does have one on his Facebook profile).

The Lead has contacted Reform UK for a comment regarding the incidents listed above but has received no comment by the time of publication.

Transparency laws are there for a reason: they combat anonymous influence and foreign interference, ensure the public is fully informed, and help combat misinformation – all while keeping parties, candidates and campaigners accountable.

So, what are the rules – and what can you do if you notice they’ve been broken?

What are the rules?

Under UK law – particularly the Representation of the People Act 1983 and the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 – any material “which can reasonably be regarded as intended to promote or procure electoral success at any relevant election” is required to carry an imprint.

An imprint must identify the promoter (who published the material), any person on whose behalf it is published, and (for printed material) the printer, including names and addresses.

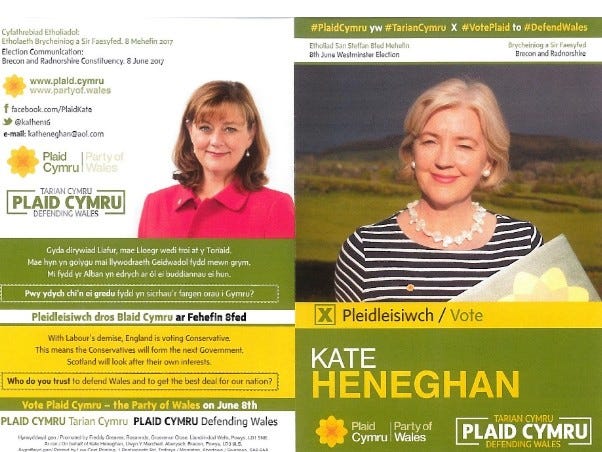

This applies to both printed and, since 2022, digital material. Printed election material refers to things such as leaflets, posters, flyers, adverts and billboards.

Imprint at bottom of first page:

Digital material, which is required to include an imprint under the Elections Act 2022, refers to paid digital adverts and organic material in campaign contexts, such as social media posts, videos and audio content posted by parties, registered campaigners and candidates.

Importantly, digital imprints must be part of the material where reasonably practicable – for example, at the end of a video. If it isn’t possible to include the imprint within the digital material – for example if the material is a very small image, it must be accessible via a clear link. It may also be in the caption or description of a post.

Imprint from the end of a video by Angeliki, the Labour candidate in Gorton and Denton:

Why does it matter?

Whether a missing imprint is a malicious attempt to manipulate voters, or a result of incompetence – the impact of not providing one is largely the same.

Imprint laws help to maintain integrity in UK democracy. They ensure voters can see who is responsible for political campaign materials and who is funding and promoting them, which helps to prevent hidden influence.

As the campaign group Electoral Reform notes, messages promoted by a seemingly unbiased source of information tend to be more persuasive than sources that clearly have a vested interest – so, making sure campaign materials are clearly labelled will help voters make informed decisions. For example, someone might be more moved by a neighbour’s letter if they weren’t aware it had been commissioned by the affiliated party.

Imprints also enable better enforcement of campaign finance and spending rules by regulators and police, because it makes those who promote the material traceable.

What are the consequences of breaking the rules?

Publishing campaign material that should have an imprint but doesn’t, can be a criminal offence under electoral law and can be enforced by the police – although the law differs for printed and digital material.

For printed material, offences are investigated and prosecuted by the police, and cases are usually heard in the magistrates’ court and can result in fines.

However, for digital material, the responsibility for dealing with breaches is split between the police and the electoral commission.

The police enforce offences where the digital material relates to the election of a specific candidate. The Electoral Commission enforces offences where the material relates to political parties, registered non-party campaigners, referendums or other regulated campaigners.

Breaking the rules can result in criminal prosecution if the police or the Electoral Commission decide to pursue it, as well as potentially unlimited fines, depending on circumstance – but prosecutions are quite rare.

How to report potential breaches in electoral law

The letter sent to Gorton and Denton residents wasn’t the first time a Reform candidate has been accused of breaching electoral law – and whether it was intended or not, the potential consequences are the same: confusion and distortion. As we enter the run up to local elections in May, keep a close eye on your local candidate’s election materials, and be sure to report anything without the necessary imprint.

If you notice election material either online or in your area that is missing a required imprint, you can report it either to the Electoral Commission or your local police force.

If it relates to a specific candidate (e.g. a local MP or councillor), you should report it to the police by using their website or calling 101. You’ll need to provide copies/screenshots and details of where and when it appeared. But, as reports have suggested, this might require some chasing.

If it relates to a political party or national campaign, report it to the Electoral Commission. You can do this via the complaints form on the Electoral Commission website. Again, you’ll need to provide evidence and explain why you believe an imprint is required.■

About the author: Ella Glover is the audience engagement editor at The Lead. She is also a freelance journalist specialising in workers’ rights, housing, health, harm reduction and lifestyle.

About The Lead Untangles: In an era where misinformation is actively and deliberately used by elected politicians and where advocates and opposers of beliefs state their point of view as fact, sometimes the most useful tool reporters have is to help readers make sense of the world. If there is something you’d like us to untangle, email ella@thelead.uk.

👫Found this edition of The Lead Untangles useful? Share it with your friends, family and colleagues to help us reach more people with our independent journalism, always with a focus on people, policy and place.

And absolutely bugger all will happen. Which is exactly what they know will happen and it's why they've done it and couldn't care less. The Electoral Commission may as well not be there it's absolutely useless