Just how disillusioned are we? The apathy crisis in stats

The data tells us disillusionment is spreading, but there is hope to be found in community and the young. Claire Miller digs into the numbers.

The people of Britain are tired. Burnt out. Switching off. That’s what we’ve noticed in our reporting around the country, and what the think tank More in Common concluded in a recent report which found disillusionment to be a “defining feature” of the public mood in the UK today. It’s why we have dedicated the entire month to tackling disillusionment, spotlighting the solutions to a rising tide of apathy.

But to get to solutions that will actually stick, we need to understand the full story. Just how apathetic are we, actually? And how does that manifest in how we live our lives and contribute to society?

Claire Miller looked into the data to understand just how disillusioned we have become and how it is affecting political and public life – and found that while the way people are understanding and engaging with politics is changing, there is a real cause for hope.

With young people at the forefront of this shift, the research shows that engaging them in political and civic life from a young age could be the solution to turning the tide on political apathy. And that’s just one of the findings uncovered by Claire’s data analysis.

The warning signs

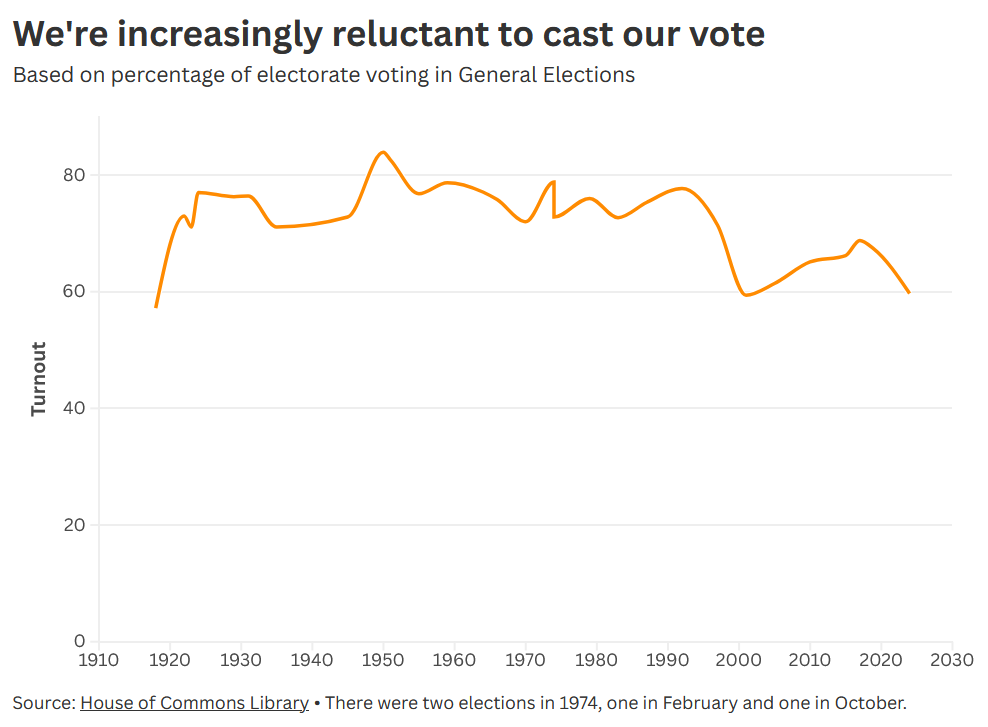

Voting is down

When it comes to politics, people are voting with their feet. Just three in five of those eligible to vote (59.7 per cent) in the 2024 General Election actually did.

That was the third lowest turnout since 1918, when turnout was 57.2 per cent, and after 2001, when it was 59.4 per cent.

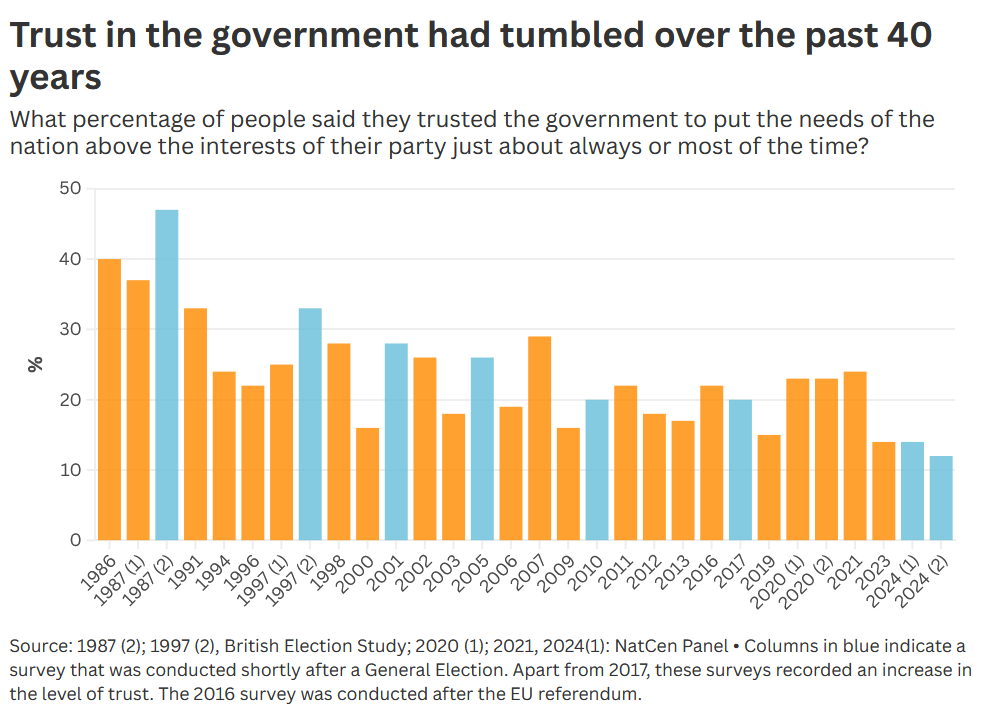

People don’t trust governments to put the nation first

Trust in the government and politicians is at its lowest level on record. Just 12 per cent of people in 2024 said they trusted the government to put the needs of the nation above the interests of their party always or most of the time.

Labour didn’t even get the post-election ‘benefit of the doubt’ boost new governments used to receive.

Does disillusionment actually make us less likely to vote?

Lack of trust and a feeling that parties were all the same or didn’t represent their views were common reasons why people didn’t vote in the 2024 election.

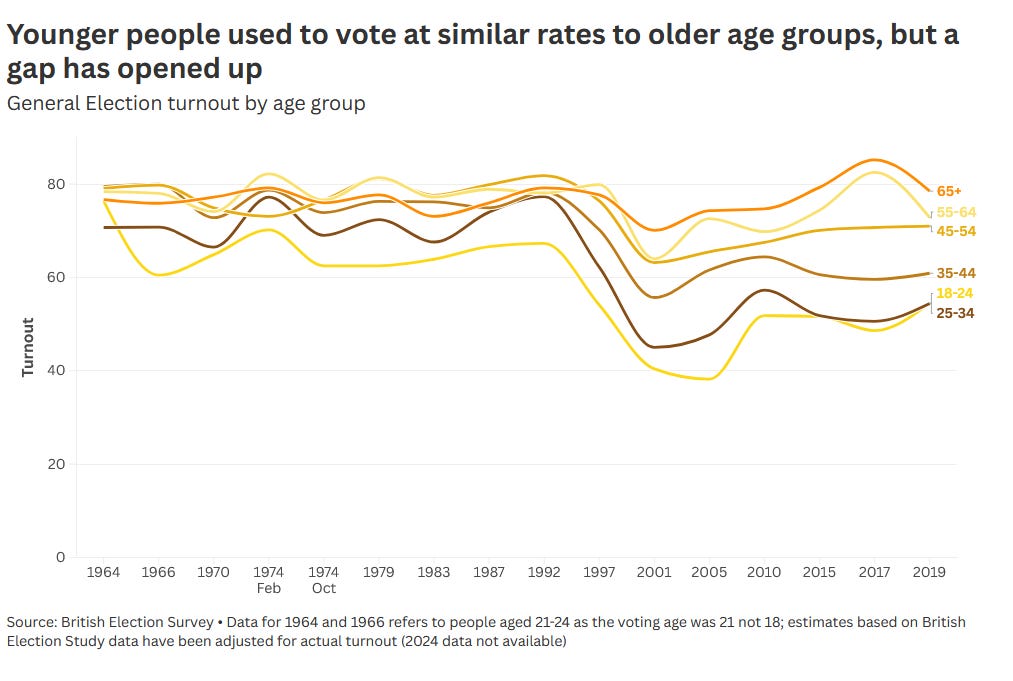

Although it’s older people who were more likely to say they were too disillusioned to vote, according to the Electoral Commission survey, this isn’t having an affect on the overall number of people in this age group voting, with young people now much less likely to vote than older.

Research by the National Centre for Social Research, found those who said they “almost never” trust governments were only slightly less likely to say they had voted than those who trusted them at least “most of the time”.

Low voter turnout driven by people who are disengaging

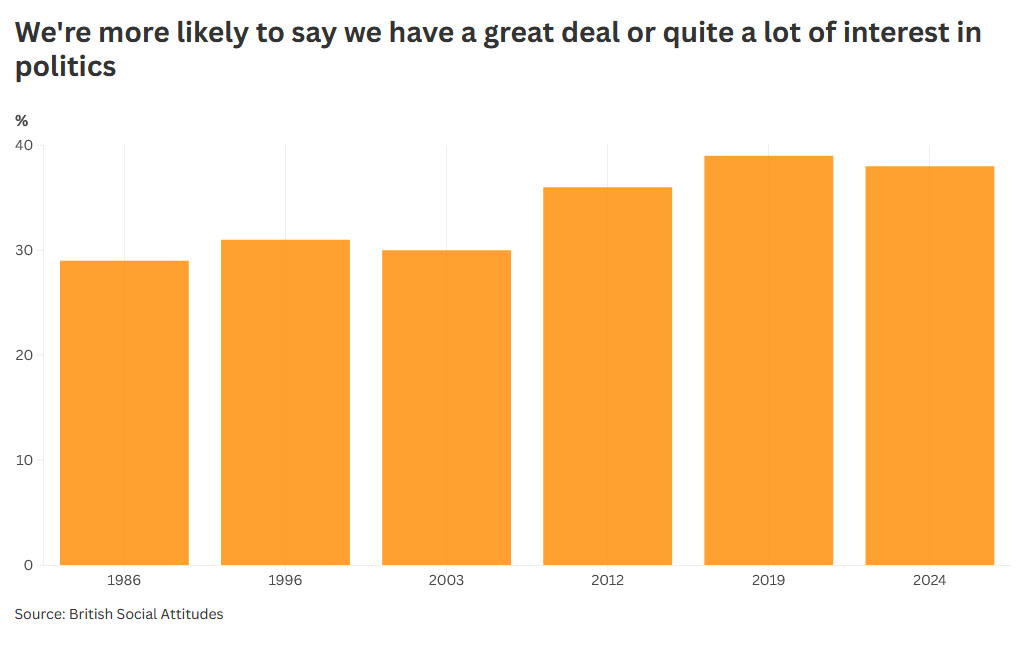

Although voting turnout is down, more of us would say we’re interested in politics than 40 years ago. The problem seems to be that those with less interest are now less motivated to vote.

In contrast, turnout did not fall at all among those with “a great deal” of interest in politics and only dipped from 94 per cent to 90 per cent among those with “quite a lot” of interest.

With just 22 per cent of all adults under 35 saying they are very or fairly interested in politics, compared with 33 per cent of those aged between 35-54, and 46 per cent of those aged 55 and over, this might be a reason young people are less likely to vote.

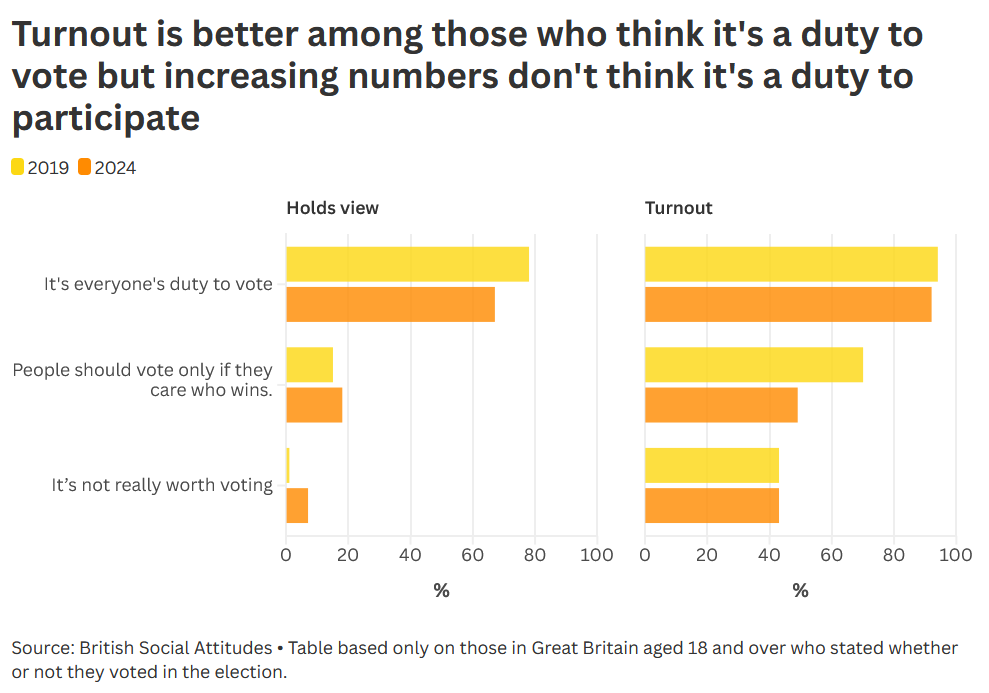

We may also be more apathetic about the importance of voting. If someone thinks voting is a civic duty, they’re more likely to vote. More than 90 per cent of people in this group voted compared to less than half who don’t think they have a duty to participate.

But fewer of us think it’s our duty to vote. Two-thirds (67 per cent) of people of voting age said they had a duty to vote in 2024. In contrast, over three-quarters (78 per cent) felt that way in 2019.

Following the 2024 election, just over half of those aged 18-24 (56 per cent) said they voted because it was important for their civic duty, compared to 74 per cent of those aged 65-74, and 75 per cent of those aged 75 and over.

Reasons to be positive

Many of us still have a strong sense of community

Most people (81 per cent) think where they live is somewhere people from different backgrounds get on well, a view that’s remained fairly consistent over the past decade.

The pandemic did seem to boost community connection. And for people’s sense of belonging to their neighbourhood, the effect seems to have continued.

It peaked in 2020/21, with two-thirds (65 per cent) saying they had a fairly or very strong feeling of belonging. It fell back to 62 per cent by 2024/25, but that’s still higher than 2014/15.

Lots of us do get involved

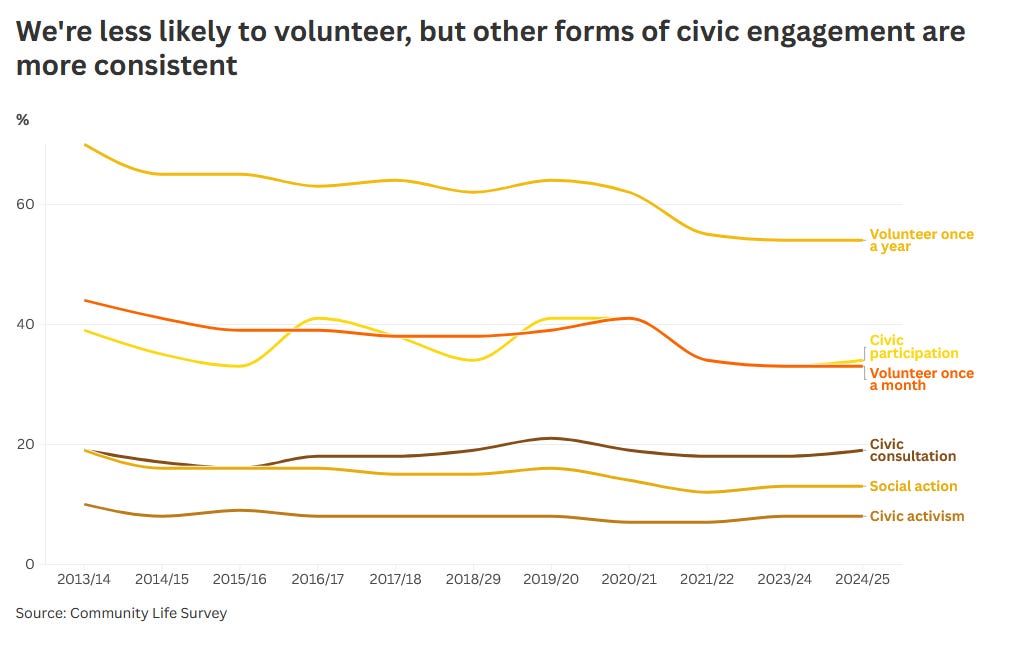

Two-thirds of us (66 per cent) are engaged in our communities. We’re signing petitions, getting involved in decision making, volunteering, and taking action to make things happen.

Civic consultation, which includes going to a public meeting or filling in a questionnaire, has been more stable over the past decade. A fifth of people (19 per cent) took part in civic consultation in 2024/25.

Becoming a councillor, school governor, or joining a decision making group counts as civic activism. Only 8 per cent of people did this in 2024/25, although this level is mostly stable.

Volunteering is more common. A third of people (33 per cent) volunteer at least once a month, and just over half (54 per cent) volunteer at least once a year. This includes formal volunteering through clubs or groups or informal helping others in the community.

Hope for the future

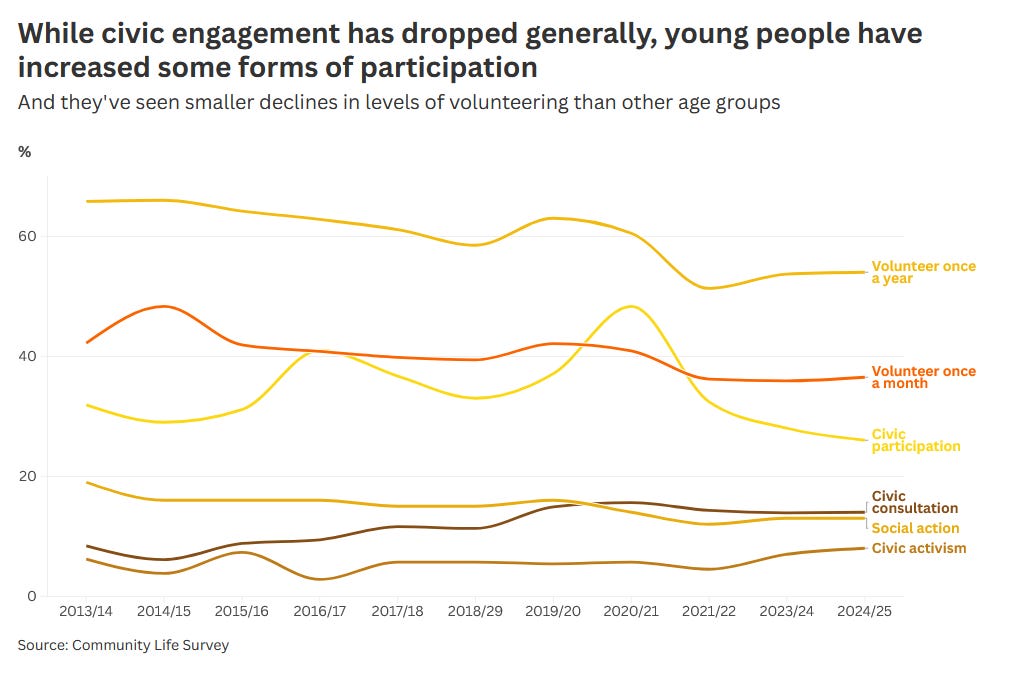

While young people are less interested in politics and less likely to vote, the data suggests labelling them apathetic and disillusioned would be unfair.

They’re often the age group that’s least engaged in their local community. But unlike other groups, they seem to be getting more connected.

Those aged 16-24 are among the least likely to feel strongly that they belong to their immediate neighbourhood – at 56 per cent in 2024/25, compared to 62 per cent overall. But that was the strongest sense of belonging for this age group since the survey began in 2013/14.

For 16-24-year-olds, participation in civic consultation (going to public meetings etc.) has risen from 8 per cent in 2013/14 to 14 per cent in 2024/25. For those aged 75 and over, it dropped from 24 per cent to 17 per cent.

Again, young people are increasingly likely to take part in civic activism (joining decision-making groups). Participation rose from 6 per cent in 2013/14 to 8 per cent in 2024/25, while it fell from 15 per cent to 10 per cent for those aged 65 to 74 and from 11 per cent to 8 per cent for those aged 75 and over.

They’re also among the keenest volunteers. Nearly two-fifths (37 per cent) of 16-24-year-olds volunteered at least once a month in 2024/25, beaten only by those aged 65 to 74 (40 per cent) and 75 and over (37 per cent).

Are young people key to improving levels of disillusionment?

How interested we are in politics (and subsequently how likely we are to start voting) might be set in our teen years.

One study found differences in people’s party identification and political interest are already clear at the end of their teenage years and remained constant through their twenties.

Gaps in interest that develop in these years also stick. Another study found, at age 11, children from the most and least educated families share a broadly similar level of interest in politics.

But by age 15 the political interest of children with the most educated parents remained the same. For those from the least educated families, it had fallen. This gap was still there when the group reached 30.

Those from more disadvantaged backgrounds are already less likely to vote.

A survey by Ipsos after the 2024 election estimated turnout at 45 per cent for people in families where the chief household earner is a semi-skilled/unskilled manual worker or unemployed. Turnout was 67 per cent for those in families where the chief household earner has a professional or managerial job.

University-educated parents influence their children’s political interest through things like taking their children to museums or art galleries, or choosing schools more likely to encourage classroom discussions and political activities. Pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to attend schools that offer this.

So the problem may be that children and young people don’t lack interest or a desire to change things, but lack opportunities to be heard.

Just 31 per cent of those aged 10-21 agreed their voice matters for decisions made in their local area, compared to 38 per cent who disagree, according to a survey commissioned as part of the Government’s National Youth Strategy.

Only 26 per cent agree their voice matters for decisions on a national level, while 49 per cent disagree.

In its Good Childhood Report 2025, the Children’s Society found that young people were keen to be involved in changing things for the better. And research for the National Youth Strategy found that when young people do not feel listened to by politicians, they are also less likely to participate in politics and civic engagement.

Nurturing children’s interest in politics might make them more likely to vote. And starting young might mean they keep the habit. Research shows voting in one election makes a person more likely to vote in future elections.

Scotland lowered its voting age to 16 ahead of the independence referendum in 2014, and for all Scottish elections starting in 2015. Those aged 16 and 17 at their first election were more likely to vote than those aged 18 and 19. And that boost in participation carried on for later elections.

So, with a commitment to lower the voting age to 16, increase civic and political education, and give young people more say on services in their area, the Government’s recently launched National Youth Strategy might prove an opportunity to build a less disillusioned future.■

About the author: Claire Miller is a freelance journalist who specialises in using data and the Freedom of Information Act in her reporting.

The Hope Reset is our January series that aims to help you start the year on an optimistic note. Ditch the doom-scrolling and tap into something hopeful instead. Cutting through the apathy of our times starts with you. Thank you for reading.

Subscribe to The Lead in January and get a huge 26 per cent off annual membership, which means it’s just £36.26 instead of £49 for the whole year.

This data is realy powerful. I've seen the disengagement firsthand with younger family members who just dont feel like their vote matters anymore. The point about political interest being set in your teens makes so much sense, and lowering the voting age to 16 could genuinely help break that cycle of apathy.

Our anti-democratic "First past the post" electoral system carries a lot of the blame. For so many people it doesn't matter how they vote - it cannot make a difference. Bring in PR and every vote will count.