Britain once saved my grandfather. Would it save him now?

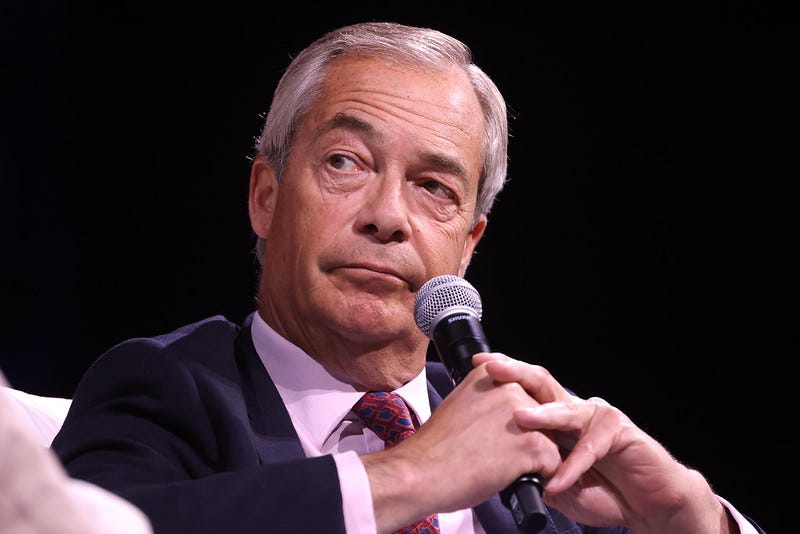

Nigel Farage's plans for mass deportations are a test of our humanity.

Earlier this year, I was chatting to a Reform insider, someone who (if the party’s polling continues to rise) could find themselves in a formative, perhaps even ministerial, role in a future Reform government. On the topic of immigration, I asked about the prospect of mass deportations, something the party’s fringes had been muttering about. They shook their head. “It’s political suicide,” they told me. “You can’t sell mass deportations to modern England. It’s a non-starter.”

And yet, just months later, here we are. Nigel Farage has unveiled “Operation Restoring Justice,” a plan that would see hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children rounded up, detained on military land and deported on a rolling schedule of flights to the countries they fled, or to third states willing to take British taxpayer money, like Rwanda or Albania.

It is not only new arrivals that would face deportation, but also people who have lived here for years without papers. To enable this, Reform UK proposes leaving the European Convention on Human Rights, and disapplying the Refugee Convention, the UN Convention Against Torture, and more.

What does this all mean in practice, aside from mass deportations of children, the creation of concentration-camp-style facilities, and a blanket refusal to provide refuge to anyone who arrived here without permission?

For me, this question is personal. My paternal grandfather, Heinz, was a German-Jewish child who arrived in Britain on the Kindertransport, part of the last lifeline for Jewish children fleeing the Nazis. He was welcomed here when his own state murdered his parents and branded him unwanted. He built a life, raised three children, and contributed to the country that gave him sanctuary. Without that thin thread of compassion and internationalism, I would not exist. (When I once mentioned this on GB News, one viewer wrote in to say it only proved their point: had Britain not accepted Jewish refugees, I wouldn’t be here today ruining their Friday night viewing. A reminder, perhaps, of just how far the conversation has sunk.)

Under Farage’s Britain, of course, my grandfather might not have made it. He might have been detained in a camp, shunted back across the Channel into the hands of the Nazis, or told his life was worth less than the paperwork he lacked. It seems to me that enough time has passed, and enough rhetoric left unchecked, that severing ourselves from international law designed to prevent a return to Europe’s darkest history has started to be presented as a logical, even reasonable conclusion, to the number of people seeking asylum in this country.

That is not to say our asylum system works as it stands. It clearly doesn’t; processing is slow, safe and legal routes are scarce, and border security fails to document everyone crossing. But the solution to these problems requires political bravery: establishing safe routes, speeding up processing, and closer cooperation with our European neighbours.

Farage’s scheme is unworkable on a scale that makes even the Conservatives’ Rwanda plan look modest. Tearing up our international obligations would have untold consequences, not just for our standing in the world but for the Good Friday Agreement too. It would put us on a slippery slope, stripping away all of our protections of international law. We too would see the framework that shields us from arbitrary detention, torture, and abuse disappear before our eyes.

Beyond unworkability, it is inhumane. It requires us to stop seeing asylum seekers as people but as a logistical issue. It also normalises the idea that compassion is “woke”, that those unlucky enough to be born into danger deserve no refuge. When Farage shrugs that Britain “cannot be responsible for everything that happens in the whole of the world,” when asked whether deported Afghans might be tortured or killed, he isn’t being pragmatic; he is shifting the moral goalposts. Obviously, no one asked Britain to solve every crisis; only that it not actively deliver the vulnerable back into the palms of those who would harm them.

We have reached this point not because the public demanded cruelty, but because cruelty has been gradually normalised. First came the rhetoric about “invasions” and “illegals” from serving government ministers, then came the barges and the Rwanda plan. Now we are talking openly about concentration-style camps and mass flights.

This is not who we are, it is what we have become. Britain’s proudest moments came when we opened our doors to the Kindertransport children, the Ugandan Asians, those fleeing war in the Balkans and Ukraine, to name a few. The European Convention on Human Rights, drafted in the aftermath of the Holocaust with heavy British involvement, was done so with wide, tired eyes, in collective astonishment at how quickly Europe slid into fascism.

We must resist Reform UK’s stripping away of our humanity and the lie that it is naïve to want to protect people from harm. Every day we play Farage’s game, we risk becoming a country unrecognisable from the one that once opened its doors to my grandfather and 10,000 other Jewish children, whose lives were spared because Britain still knew compassion.■

About the author: Zoë Grünewald is Westminster Editor at The Lead and a freelance political journalist and broadcaster. Zoë then worked as a policy and politics reporter at the New Statesman, before joining the Independent as a political correspondent. When not writing about politics and policy, she is a regular commentator on TV and radio and a panellist on the Oh God What Now podcast.