"It's the Hunger Games": SEND children are being failed in mainstream schools

The government has pledged more money to improve special needs education – but desperate families say the whole system needs overhauling.

For a year, Freya turned up at primary school and was illegally restrained – not because she was a danger to anybody, but because the effort of masking her autism in the school environment made her want to run back to her mum every morning. For her, the mainstream education system became a source of trauma.

Freya is just one of the 1.7 million children in the UK with special educational needs and disabilities [SEND] who are battling a broken a system. Many face significant barriers to education – from struggles to get a diagnosis that will unlock support, to inaccessible school buildings, negative attitudes, and modes of learning that are not adapted to their needs. This leaves children stuck in unsuitable environments, out of education for long stretches of time, or pushed out of education entirely.

28 per cent of SEND students currently have an Education Health and Care Plan [EHCP] and the remaining 72 per cent are receiving SEND support without an EHCP. An EHCP is a legal document that identifies the support a child needs – things like individualised teaching methods, additional staff support, or speech and language therapy. But children and parents face lengthy waits for these plans.

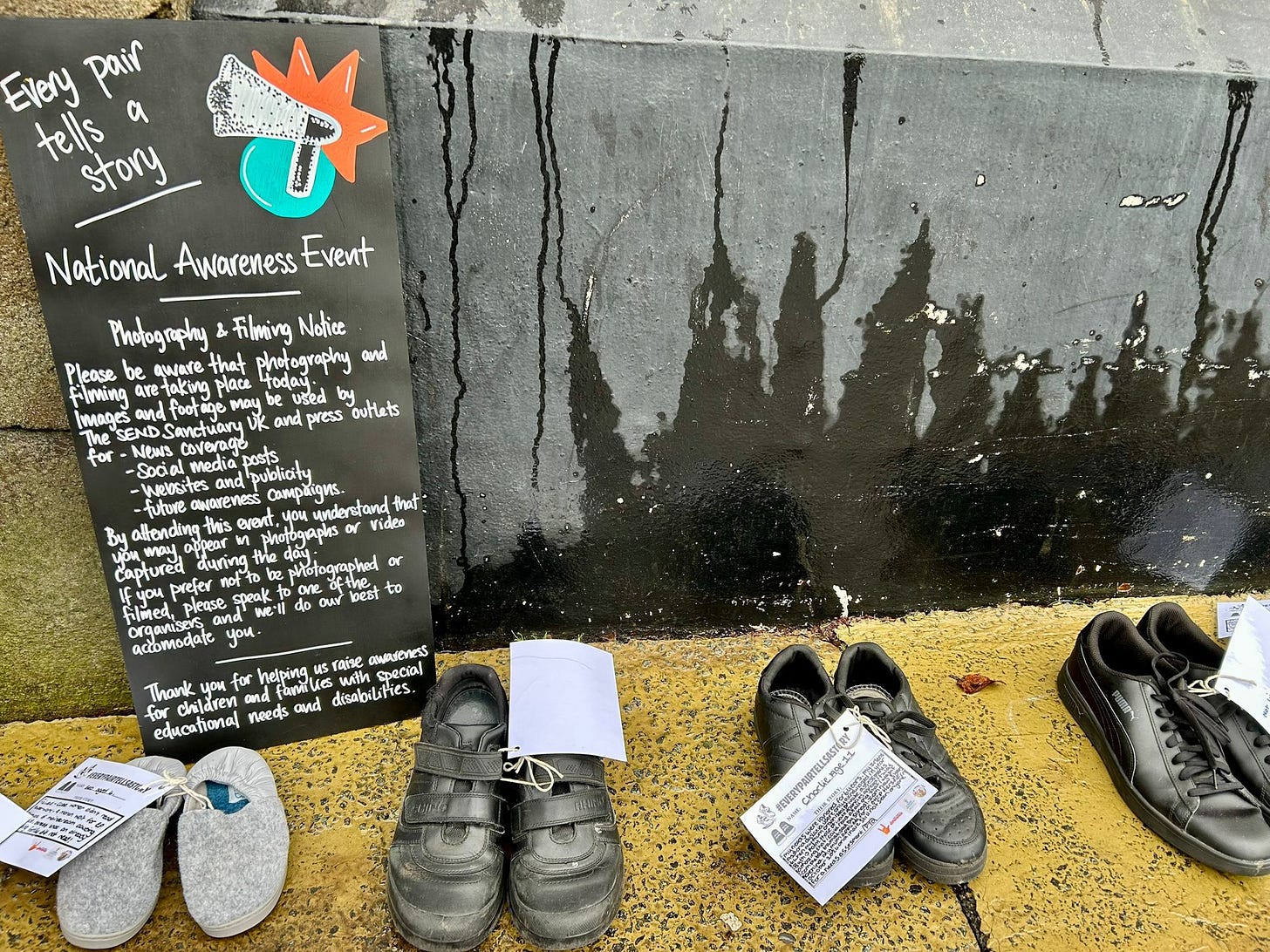

This is a national crisis of children being failed by their local councils and not receiving their right to an education. It is left to family members – like Freya’s mum – to advocate for their child’s education. Recently, these desperate circumstances have led to nationwide protests by family and advocacy groups. These protests gave visibility to the children who have been failed by the SEND system – but more needs to be done.

The government has pledged to improve accessibility of mainstream school buildings and provide more specialist places within mainstream schools. However, the support currently offered is insufficient. Real change will only come through proper reform of how children are taught, recognising that SEND students are not a homogenous group but real children with individual needs and ways of learning.

Tear it up and rewrite it

Helen is a mum of two neurodivergent girls from Devon who believes an overhaul of the mainstream system and curriculum is needed. Helen’s eldest daughter Freya*, now 17, started struggling years before being diagnosed.

“Back then, there was very little understanding of ADHD in girls and practically zero understanding of masking,” explains Helen, because headlines around neurodiversity typically focused on boys.

Masking is a strategy some autistic people use, consciously or unconsciously, to appear non-autistic and be more accepted in society. This can, among other consequences, lead to physical and mental exhaustion and a loss of sense of self, as well as delaying a diagnosis of autism.

As a result of masking in school, Freya’s mental health was severely suffering outside of school. When Freya was being “illegally restrained” to prevent her running back to her mum at drop-off every morning at primary school, a GP stepped in and signed Freya off sick.

The family embarked on a struggle to get an EHCP but the Local Educational Authority [LEA] tried to push Freya back into mainstream education, which Helen describes as the “original site of the trauma.” This lack of support from the LEA forced the family to go private for diagnoses and a more in-depth educational psychologist report.

Legally, local authorities have 20 weeks from when they receive a request for an EHCP assessment to issue the plan. However, in 2024, only 46.4 per cent of EHCPs were issued within the statutory timeframe. After a year, Freya eventually received hers.

“There’s zero accountability in the system,” explains Helen. “She has been to three specialist schools. Not one of them has properly followed the EHCP and never once has the LEA, upon me telling them that, actually held that school to account.”

Helen describes her fight for Freya’s education as “the Hunger Games,” leading her to view the school system differently. “The system is set up that attendance is king,” explains Helen, highlighting the dominant pressure of Ofsted in determining a school’s attitude and curriculum.

Helen would like to see changes to mainstream education, to modernise the syllabus so it is more collaborative and less focused on remembering and regurgitating information in exams. Most importantly, she wants to see education that prioritises a “child at the centre” approach, a learning model that follows the interests, abilities and motivations of the individual child.

“Just tear it up and rewrite it,” is what she’s proposing. “It inhibits creativity and free thinking. Everyone should have a chance to shine because everyone’s got that ability. But this system doesn’t allow for that. Arts, music, those kinds of things, are just not valued.”

The shortage of specialist support

After moving around a number of specialist and private schools, Freya is now largely taught at home on a personal budget which allows parents to have a say in how the local authority spends the money on their child’s education. Helen bespoke designed an education for Freya and put the costings forward to the LEA who decided what funding they would agree to.

This provides Freya with an education that is more tailored to her needs consisting of [among other support] time with tutors, online learning for academic subjects, resources, and a vocal coach. However, Helen describes how she has noticed a “clamping down” on personal budgets over the years, stating that when she reapplied for Freya’s personal budget two years ago, many of the things she had previously asked for were not agreed.

The impact on Freya’s life has been huge. “Her education is completely obliterated. She still has a learning phobia from school and she’s way, way, way behind. She has no reason why she wouldn’t be able to, intelligence wise, do a degree if she felt like it, but she’s still at primary level in terms of her knowledge base because she’s not had an education for six, seven years,” Helen describes.

Helen’s younger daughter, Gabby, is also neurodivergent and attends a SEND school with an EHCP. However, Helen points out that there are too few specialist schools meaning they are “pulling too many children in” and “compromising the quality of what they can deliver.”

Department for Education figures show that, last year, around two thirds of specialist provision secondary schools were at or over capacity. This meant there were 8,000 more pupils in special schools than places available for them – a number that is set to rise. To ease the strain on the number of specialist places available, the government announced £740m of capital funding in the Spring 2025 budget to create 10,000 specialist places in mainstream schools.

The funding is to adapt classrooms to be more accessible and create specialist facilities with more intensive support within mainstream schools. Undoubtedly, this will aid some students in accessing more supportive mainstream education, but stories like Freya’s show the need for widespread reform of how students are taught and the environment they are taught in.

The creation of more specialist spaces in mainstream schools only makes a difference if it is accompanied by meaningful reform created with the input of SEND students and their parents.

Long waits for answers

Abby, a parent of an autistic child from Manchester, had a more positive experience with her son Ben, in a mainstream secondary school once support tailored for him was put in place. But the process was not without difficulties.

Ben struggled in school from a young age but without a diagnosis, getting extra support was difficult. Abby paid privately for an Autistic Spectrum Disorder [ASD] assessment for Ben because “an assessment through the local authority was going to take two or three years of being on a waiting list”.

Between 2022 and 2023, children referred for an autism assessment by mental health services waited, on average, one year and five months for an appointment, and children referred by community health services waited two years and two months, forcing many parents to turn to private healthcare providers.

After Ben received a diagnosis of ASD, Abby was “flabbergasted” when his primary school refused to support an EHCP application. It was only when Ben transitioned to secondary school that support improved.

“School has been really good in raising awareness [..] with their pupils about ASD,” says Abby. This time, the school did support the application for an EHCP and it was approved, unlocking access to specialist support, teaching assistants and extra academic interventions.

Abby puts their positive experience down to Ben’s secondary school Special Educational Needs Coordinator [SENCO] who has experience of ADHD in the family, giving her the ability to understand some of the challenges facing neurodivergent children in schools. “You have to get the right people in the job and [Ben’s SENCO] is obviously the right person,” she says.

In May, the government refused to rule out removing EHCPs in mainstream schools, drawing criticism from concerned parents, charities and campaigners. Abby notes that Ben’s EHCP has “without a doubt” improved his mainstream education.

Support should be needs based

Caitlin, a SENCO from Stockport, works in a small mainstream school that caters for children with EHCPs and those on the SEND register without an EHCP. Caitlin’s school is also funded for nine resourced provision places – a specialist unit within a mainstream school that provides more intensive support.

Caitlin is proud of the inclusivity of her school. The equipment for the four students who are wheelchair users are “scattered around school, very normal to be about” and dual coding (pictures and written language) is everywhere.

“Our environment is very calm,” says Caitlin. “It’s a very low stimulation environment, very deliberately.”

The school’s main mission is inclusion, not results, and Caitlin believes in a “needs-based” approach to education. However, the school faces a big problem: money.

“The local authority doesn’t adequately fund what their provision is. We’re always looking at deficit budgets and where we can lose staff,” says Caitlin.

County Councils Network has warned that the deficit from SEND education for councils has grown to £6 billion nationally.

For some, the mainstream system works when the correct support is put in place but for others, it is still unsuitable, traumatic or adversarial. While the government is looking at reforms to EHCPs, parents and children with SEND hope they will look at the system as a whole to ensure that every child’s right to an education that is suitable for them is upheld and improved.

Helen knows the discrimination and barriers children with SEND face in education impacts their whole lives. She believes a failure to fix the exclusionary, broken SEND system is short-sighted, and creates a situation where it is more likely that children who have been through the system will need government support in the future.

Like many parents who have battled the system, Helen is desperate to see a change. Too many children are failed by a system that pushes them into a mainstream schooling environment that is unsuitable and traumatic for them, or provides them with too little support.■

*Names have been changed.

About the author: Tiger-Lily Snowdon is a freelance writer and student with lived experience of chronic illness and disability. She has an interest in disability rights, gender equality and human rights. She has previously been published in The Guardian, The i Paper and Shout Out UK.

There has never been a better time to join us. Support independent journalism for less than £3 a month by subscribing and get a 30% discount on annual membership – only available until the end of November. The Lead exists because readers believe in what we do – and because you are willing to stand with us to fight for a more optimistic future for all.

If you enjoyed reading this article please share this post to help us reach more people with our nuanced, independent journalism that covers the stories that matter to you.