The Lead Untangles: Facial recognition technology - surveillance state or crucial police tool?

An invasion of privacy or a much-needed way to keep people safe at major events? As the Home Office consults on the use by police forces we explore the history and current usage

The Lead Untangles is delivered via email every week by The Lead and focuses on a different complex, divisive issue with each edition. The entirety of The Lead Untangles will always be free for all subscribers.

Get beyond the headlines and make sense of the world with The Lead Untangles direct to your inbox. And support us to get into the people, places and policies affecting the UK right now by becoming a subscriber.

At a glance facts

The Home Office wants to significantly expand police use of controversial facial recognition technology.

Launching a consultation last month to inform a new legal framework for the technology’s use, the Home Office said the government is “focused on enabling more police forces to safely expand their use of facial recognition”.

Policing and crime prevention minister Sarah Jones calls facial recognition technology a “valuable tool to modern policing” but claims to understand “legitimate concerns” and “significant doubts” about the state’s powers to process citizens’ biometric data and the police acting proportionately.

The framework will cover the three types of technology police already use – retrospective facial recognition, live facial recognition and operator initiated facial recognition.

But it will also address the potential future use of biometric, inferential and object recognition tools that could be used to predict individuals’ emotions and behaviour, such as criminal or suicidal intent.

Context

Facial recognition technology has been in use in the UK since the 1990s, following the rapid growth of CCTV cameras for surveillance.

Newham Council linked it to CCTV cameras in the East London borough in 1998, its computer fed with images of convicted local criminals. If the system detected a match from its cameras, it alerted an operator who in turn alerted the police, who decided what, if any, action to take. Four years later it hadn’t made a single match and the scheme was later dropped.

Leicestershire Police became the first force to trial the Neoface system in 2014, allowing it to match camera images to its 92,000-strong database of people it had arrested or who had given permission for their photos to be stored – but not in real time.

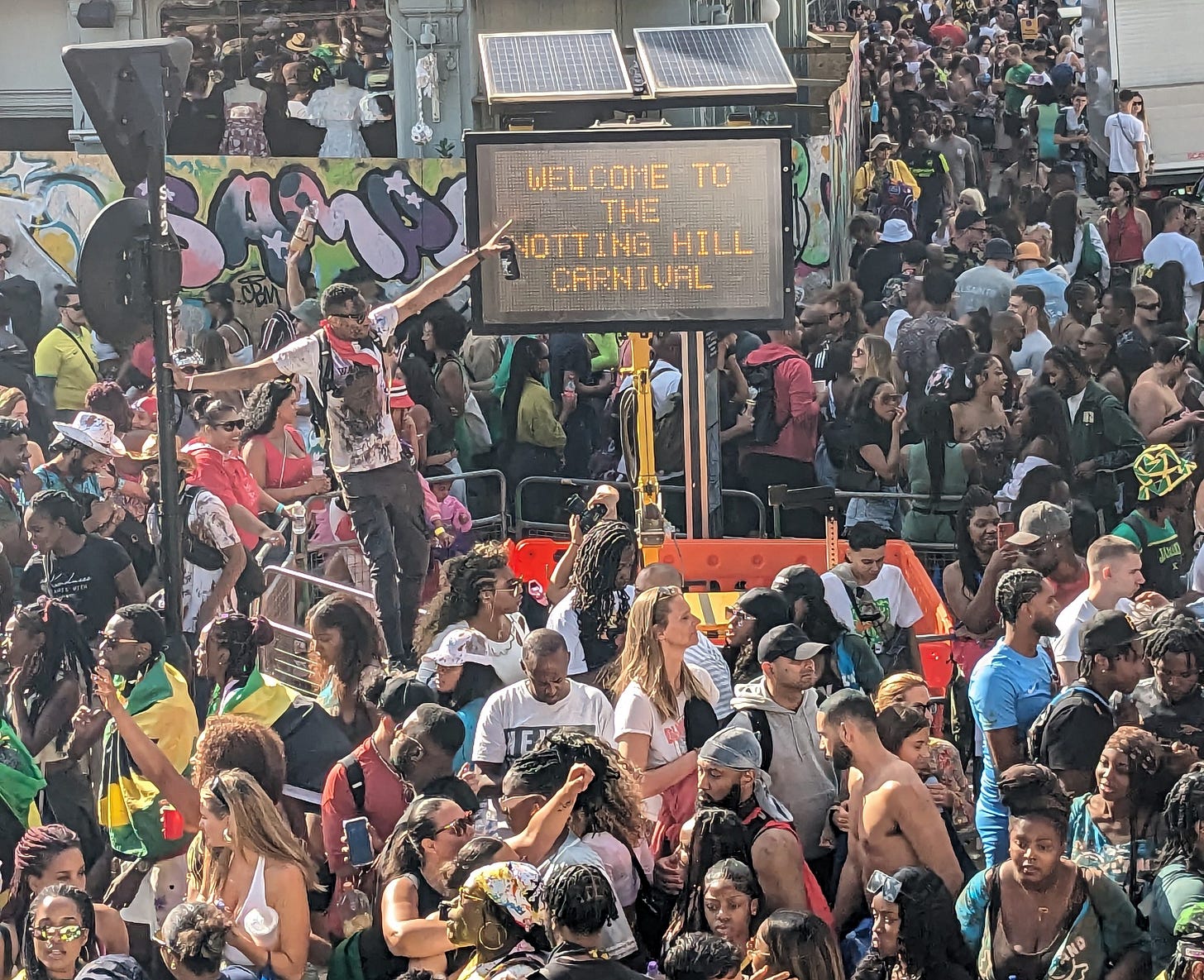

After the force then deployed live facial recognition at the Download festival in 2015, checking rock and metal fans against known suspects, the Metropolitan Police followed suit with a trial at the 2016 Notting Hill Carnival, as did South Wales Police at the 2017 UEFA Champions League Final in Cardiff.

The deployment led to widespread criticism from regulators, researchers, civil liberties groups and individuals directly affected. And even South Wales Police’s own data showed the UEFA trial got 92 per cent of its matches wrong.

The first annual report from the new Biometrics Commissioner in 2014 expressed alarm that 12 million custody photos had been uploaded to the Police National Database, with an automated search mechanism.

Pointing out that the database had none of the controls or safeguards that applied to DNA and fingerprint databases, the Biometrics Commissioner warned against the storage of images of people who hadn’t been convicted of a crime, the indefinite retention of images, and the lack of proof of the technology’s reliability.

A US government report in 2019 suggested that facial recognition algorithms were highly inaccurate in identifying African-American and Asian faces compared to white faces. African-American females were even more likely to be misidentified, said the report. That year the Commons Science and Technology Committee unsuccessfully reiterated its call for a moratorium on facial recognition over its “effectiveness and potential bias”.

And in 2020, civil rights group Liberty won a legal challenge at the Court of Appeal on behalf of Cardiff resident Ed Bridges, forcing South Wales Police to end its trial because of breaches of privacy rights, data protection laws and equality laws.

Liberty lawyer Megan Goulding said: “The Court has agreed that this dystopian surveillance tool violates our rights and threatens our liberties.”

Yet with new police guidance and the insistence by its makers that the tech had been improved, the use of facial recognition continued to expand. According to the Home Office, as of November 2025, 13 police forces have used or are using live facial recognition.

One of the most recent is Greater Manchester Police, which last November initially deployed two vans in Sale.

Inspector Jon Middleton said the vans were placed where there was a “policing reason – for example shoplifting or neighbourhood crime”, but no arrests were made.

He claimed people “have generally been happy to see us and speak to us, and supportive of the way the technology is being used”.

The Home Office says retrospective facial recognition has led to a number of suspects being caught, including 127 in August 2024 during the riots following the Southport stabbings.

It says the Metropolitan Police recorded 962 arrests for offences including rape, domestic abuse, knife crime, grievous bodily harm and robbery as a result of using live facial recognition to locate people.

Yet the criticisms remain. Liberty points to research showing that “hundreds of children have been included on police watchlists for facial recognition deployments – with minors as young as 12 targeted by the tech”, calling for an end to the rapid rollout of the technology and stronger safeguards.

And damningly, in the same week the consultation was launched, the Home Office played down a report it commissioned from the National Physical Laboratory, admitting that in a “limited set of circumstances the algorithm is more likely to incorrectly include some demographic groups in its search results”.

Earlier last year, Shaun Thompson of the community outreach organisation Street Fathers settled out of court with the Metropolitan Police after officers misidentified him as a suspected criminal using live facial recognition.

What does facial recognition actually do?

The Home Office identifies three main uses of facial recognition technology available to the police.

Live facial recognition involves processing live video footage of people passing a camera. The images are compared against a watchlist of wanted people. It says images are deleted immediately if there is no match.

In retrospective facial recognition, images of people police seek to identify are taken from crime scenes, often from CCTV or mobile phones, and compared against custody images of people who have previously been arrested.

Only two police forces are using newer operator-initiated facial recognition, a mobile app allowing officers on the street to conduct an identity check against the custody image database.

What people are saying

Policing and crime prevention minister Sarah Jones: “Whilst it is clear there is a legal framework within which facial recognition can be used now, I believe that confident, safe and consistent use of facial recognition and similar technologies at significantly greater scale requires a more specific legal framework.”

Big Brother Watch director Silkie Carlo said: “For our streets to be safer the government need to focus their resources on real criminals rather than spending public money turning the country into an open prison with surveillance of the general population.

“Facial recognition surveillance is out of control, with the police’s own records showing over 7 million innocent people in England and Wales have been scanned by police facial recognition cameras in the past year alone.”

Sian Berry, Green MP and party spokesperson for crime and policing: “The legal wild west we have seen in the UK does need to end, and the government’s proposals will need legislation to be passed by Parliament.

“This is now a last chance for the public and MPs who care about civil liberties to have a proper say, reject the idea of total state surveillance, and put proper controls on this intrusive technology.”

What happens next?

Have your say via the Home Office consultation, which closes on 12 February.

About the author: Kevin Gopal is a Manchester-based journalist who has returned to freelancing after editing Big Issue North from 2007 until its closure in 2023.

About The Lead Untangles: In an era where misinformation is actively and deliberately used by elected politicians and where advocates and opposers of beliefs state their point of view as fact, sometimes the most useful tool reporters have is to help readers make sense of the world. If there is something you’d like us to untangle, email ella@thelead.uk.

Also from The Lead this week…

We have a defections special in ReformWatch as the Farage fax machine has been busy with signings, and it’s all one-way traffic from the Tories

Our team’s latest picks for what to read, watch and listen to for The Lead Digest - including a look at the rise of wellness culture

And the latest from our award-winning team at The Lead North, from broken council tax promises by Reform, an MP calling for lying to become a criminal offence and inside life in a house of multiple occupation in Southport

Thanks for reading and we’ll be back in your inbox on Saturday with the latest story from our The Hope Reset series as Serena Smith digs into the messy world of dating and love in 2026. Make sure you’re subscribed to receive it first.

👫Found this edition of The Lead Untangles useful? Share it with your friends, family and colleagues to help us reach more people with our independent journalism, always with a focus on people, policy and place.

Don’t forget, if you subscribe to The Lead in January, you’ll get a huge 26 per cent off annual membership, which means it’s just £36.26 instead of £49 for the whole year.