We are deep in a housing crisis – why are so many properties still empty?

New data reveals councils are barely taking over empty homes anymore, amid calls for a new national programme to bring unused properties back into use.

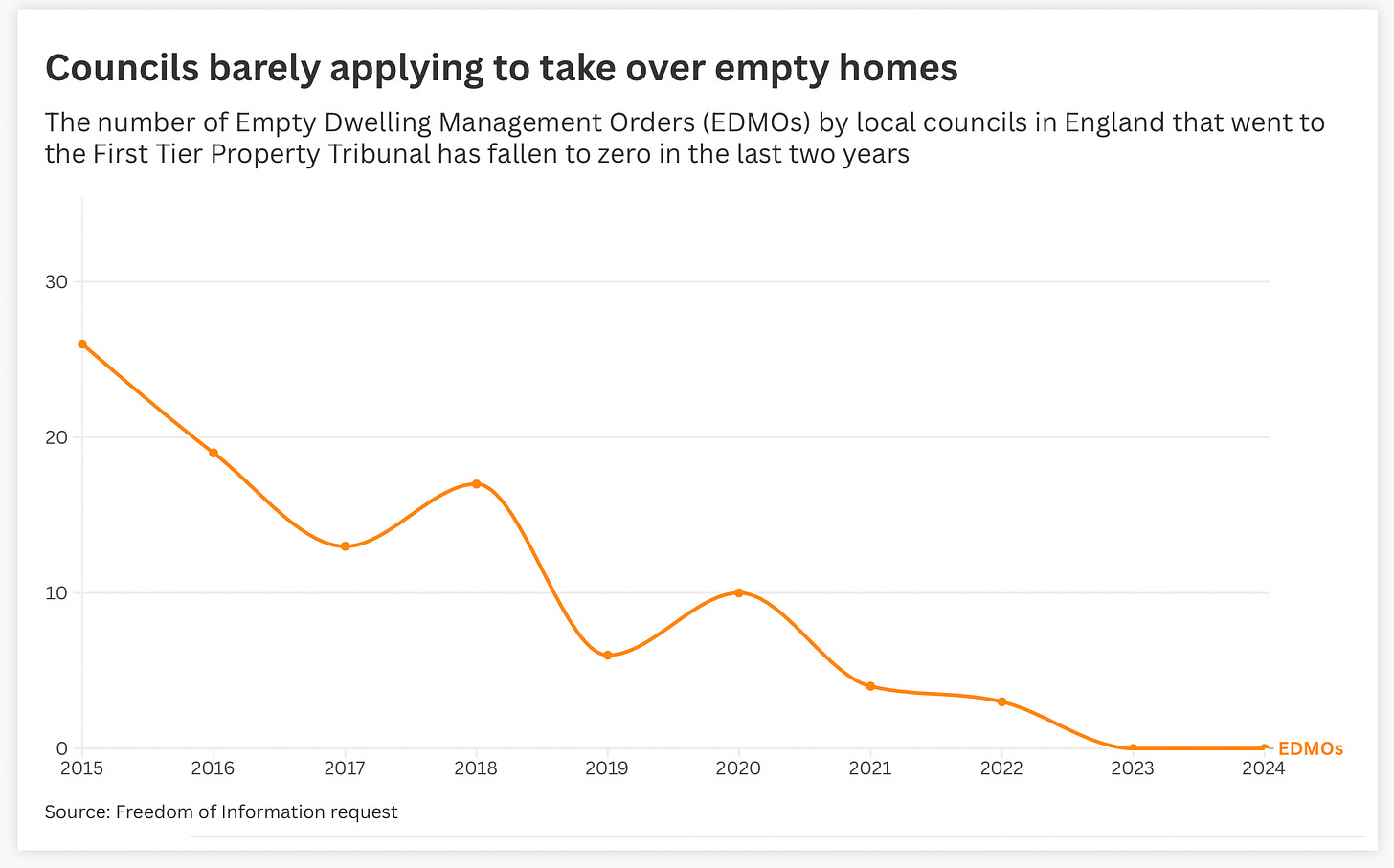

Not a single council went to court to take over the management of empty homes in 2023 or 2024, an exclusive investigation by The Lead has found.

While councils should be able to take over empty homes to house homeless families via an Empty Dwelling Management Order [EDMO], our research reveals this is simply not happening – raising serious questions about the effectiveness of powers given to local authorities to bring much-needed homes back into use.

Amid calls to reform the powers of councils to take action, others are urging the government to tackle the empty homes crisis by providing funding to offer grants to refurbish empty homes and make it easier for councils to buy them up.

For every homeless family living in temporary accommodation in England, there are two homes that have been sitting empty for six months.

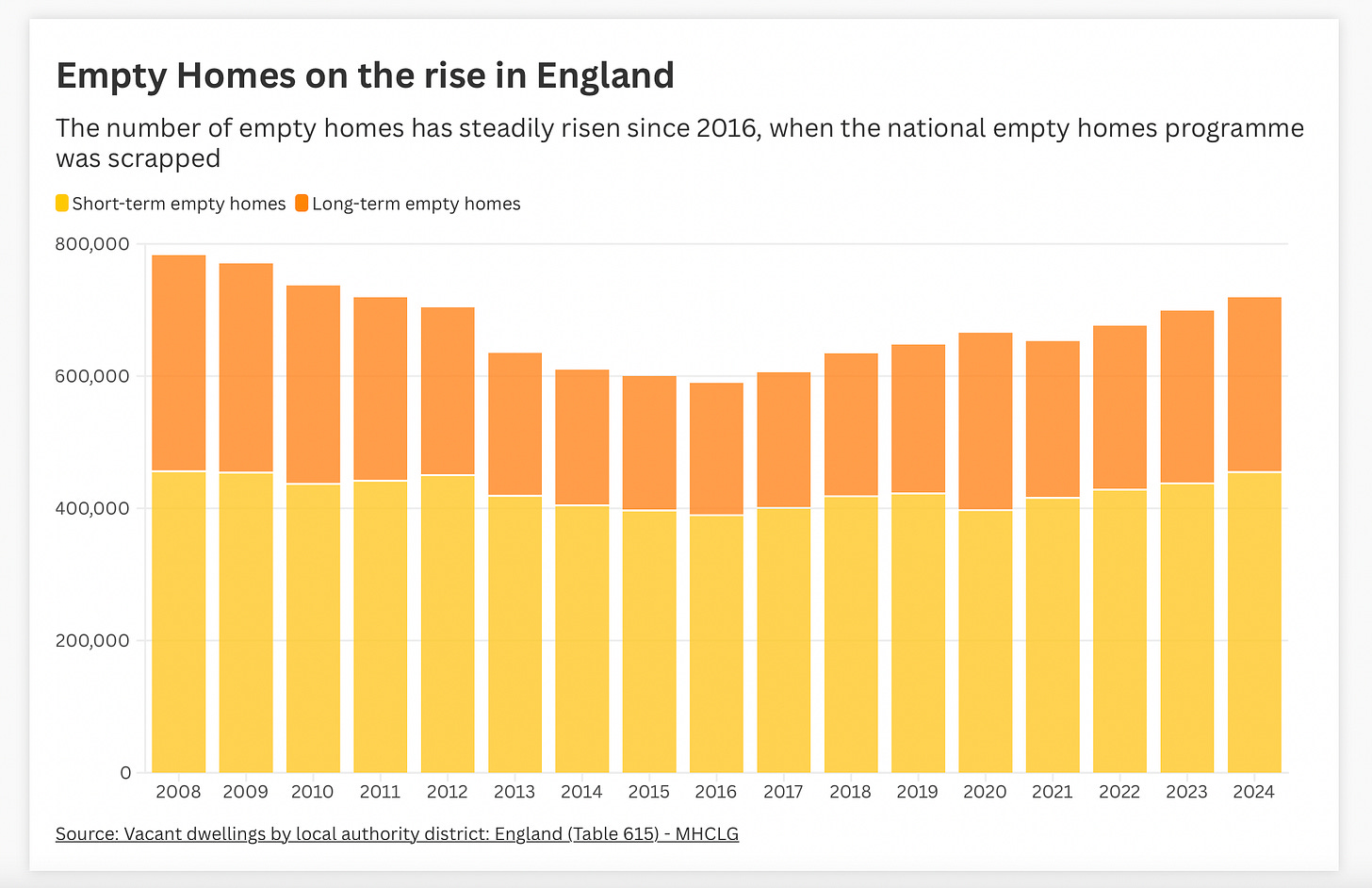

Since 2016, while the number of households needing temporary accommodation has increased by 73 per cent to record levels, long-term empty homes also rose by a third to 264,884. Empty homes are just one part of the housing crisis, but one that is increasingly seen as a key piece of the puzzle.

Can EDMOs be made more effective?

“It is incredibly disappointing that no EDMOs went to tribunal last year or the year before,” says Paula Barker, the MP for Liverpool Wavertree who organised a roundtable on fixing the empty homes crisis in 2024.

“Bringing empty homes back into use for social and affordable housing is a cost-effective and practical solution that would help prevent further families and individuals being pushed into homelessness,” she says.

Local councils can apply for an EDMO after a property has been empty for two years, which, if granted, allows them to take over the management of the property so it can be brought back into use. But the process is cumbersome and expensive for local councils, requiring evidence gathering as part of a long legal process.

Chris Bailey, from campaign group Action on Empty Homes, tells The Lead the two-year timeframe and need to convince a judge of harm to the local neighbourhood has meant the power “was never really effective”.

That’s why the Local Government Association has called for the two-year timeframe to be reduced to six months.

“The weakness of the EDMO power is that you have to wait until the home turns into a rat infestation, a crack house or a brothel, before you can do anything about it,” Bailey adds.

“We advocate for a ‘no-fault EDMO’ where you should be granted one just because the landlord has left the place empty and isn’t doing anything with it.”

However, others argue that allowing councils to apply for an EDMO after six months won’t actually help.

Adam Cliff used to be an empty homes officer at Peterborough City Council, and is now in charge of the Empty Homes Network, which has nearly 1,000 members across local government.

“If anything, bringing the timeframe forward to six months might create a wave of unsuccessful applications because the judge would want to give the owner more time,” he says.

He says empty homes officers need time to gather evidence, but the real barriers are the upfront cost of carrying out works and the financial risk to the council. One solution to this would be a pot of money that councils could use for EDMOs.

He admits that no EDMOs going to the property tribunal is “shocking” but points out this doesn’t capture cases where councils send out the three-month letters of notice to the owner, which is enough to provoke action. “I know it happens all over the country that councils threaten an EDMO,” he says.

Alternative levers

Councils can also charge double council tax on empty homes. Since 2024, this can be triggered after a year instead of two, but it doesn’t appear to be an effective disincentive.

“Broadly speaking, we know that it doesn’t really work,” Bailey says. “Because during the whole time that tax has existed, long-term empty homes have gone up by 30 per cent.”

Cliff says that the council tax premium on empty homes is having the reverse effect. “It was brought in to disincentivise owners, but what it has actually done is incentivise councils to leave properties empty for longer because they get more council tax revenue - it’s absolutely bonkers.

“We need to right that wrong, so we’re proposing that councils shouldn’t be allowed to charge the premium unless they have an empty homes officer or strategy in place.”

Cliff estimates that about half of councils have a dedicated empty homes officer, which is an optional extra on top of councils’ legal duties. But he believes councils should be forced to have an empty homes strategy and maybe a dedicated empty homes officer.

“In terms of solutions to offer owners, having an empty homes officer in every council undoubtedly would be the biggest one,” he says. “A lot of the time people don’t have the knowledge or experience to sell or rent out their property.”

He would also like to see exemptions from paying council tax – such as when someone is going through probate – to be tightened because they are currently indefinite and allow some to abuse the system.

Another solution is addressing the absurd situation in which most empty homes officers don’t even know which properties are vacant, because council tax departments cannot share ownership details under GDPR.

“We want empty homes officers to have ready-only access to council tax information to do their jobs,” Cliff says. “It’s like doing a job with a blindfold on with your hands tied behind your back in a dark room.”

The carrot of grants and loans

Alongside penalties, the owners of empty properties also need incentives, because experts warn they might be well-intentioned but lack the money to bring the home back into use.

“We think grants and loans are a gap in the market,” Bailey says, pointing to when the national empty homes programme was scrapped in 2015.

“One of the reasons we advocate for a new national programme of investment is if you put some money on the table and allow councils to choose the split between funding officers, advice, loans, and grants, then you can get targeted local solutions that work – we know it made a difference between 2012 and 2015.”

One in three councils that responded to a recent BBC investigation said they still offer grants and loans. The celebrated example is Kent County Council’s No Use Empty scheme, which has offered nearly 200 interest-free loans in the last five years. There have been calls to see schemes like this expanded across the country.

Canopy Housing in Leeds, a charity that brings empty homes back into use for homeless people. During the empty homes programme under the Coalition government, Canopy was able to buy up 15 empty homes thanks to grant funding.

Although council funding has continued since the national scheme was scrapped in 2015, Canopy is having to compete with private landlords and property developers on the open market.

“We would absolutely support a new Empty Homes Programme,” David Nugent, Canopy’s chief executive tells the Lead. “Because we’re not convinced there will be another [council] programme when this one ends in about 18 months time, so a national programme would help significantly.”

He adds thatCanopy benefits from funding because Leeds City Council gets money from Right to Buy sales, which areas with fewer council homes miss out: “The barriers are the funding and it’s a postcode lottery.”

What could a council acquisition programme look like?

The most ambitious vision for tackling the empty homes crisis is a major programme of councils buying up unused properties.

Housing charity Shelter released a report in 2024 setting out a 10-city plan to convert 10,500 empty homes into social rent homes in the first three years of a new government at the cost of £1.25bn. The plan argued that such a scheme could quadruple the building of social homes and provide better value for money than building new homes – on average by 20 per cent, which in some cities rose to 55 per cent.

Paula Barker MP says refurbishing existing properties is more environmentally sustainable and can get results quickly. “Whilst we absolutely do need more social and affordable homes built, this is a long-term answer to a crisis that we need an immediate solution to.”

She points to the “uneven playing field” where only 10 per cent of affordable housing funding outside London can be allocated to acquiring and refurbishing empty homes, compared to 30 per cent in the capital.

“The government should increase the percentage of funds that can be allocated for acquiring and refurbishing empty homes,” she says. “This would immediately provide councils with vital extra funding to address empty homes more effectively.

“Earlier this year I met with both the then homelessness minister and officials from the department to urge them to include empty homes into the upcoming ending homelessness strategy, however we have not had any updates on the matter since.”

The homelessness strategy is expected in the new year,, but the government has made very few commitments on empty homes.

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) has said it plans to ‘strengthen local authorities’ ability to take over the management of vacant residential premises’ as part of the English Devolution Bill currently going through parliament.

But what this means in practice, and whether there could be reforms to EDMO powers, remains unclear.

The Lead asked the MHCLG what its latest plans were for tackling the empty homes crisis, but the department said more detail on plans would feature in the upcoming long-term housing strategy, which it seems may now not come out until next year.

An MHCLG spokesperson said: “We are determined to fix the housing crisis we have inherited, and we know that having too many empty homes in an area can have a significant impact on local communities.

“That’s why we have given councils across the country stronger powers to increase council tax on long term empty homes, and we are considering further action.”■

About the author: Matty Edwards is a freelance journalist based in Bristol who mostly writes about housing, local politics and the environment. He was previously a reporter and editor at local media cooperative the Bristol Cable between 2018 and 2025.

👫If this article resonates with you, please comment, share and spread the word. We always love to hear your feedback, or if you have own experience to share – email natalie@thelead.uk.

🎁And if you love what we do at The Lead you can buy a gift subscription for Christmas to give the gift of The Lead to a friend, family member of colleague. There’s 20% off gift subscriptions for December and you can order right up to and including Christmas Day.

Council officers being deprived of access to council info essential to their work seems wrong. Can they do something to interpret the GDPR differently?

Well done for highlighting this issue.