Why are children still being diagnosed with personality disorders?

Young people are stigmatised and written-off from an early age when labelled with a personality disorder – campaigners want to end these childhood diagnoses.

Helen*, 26, was first put under child and adolescent mental health services [CAMHS] when she was 12. Now long-term stable – on medication, and receiving weekly therapy – she still remembers the impact of being hospitalised after receiving a personality disorder diagnosis aged 14.

“In hospital, I had a lot of diagnoses thrown at me and changed – including psychosis,” she recalls, “but the one that stuck was emerging emotionally unstable personality disorder [EUPD].”

Helen had initially received care for anorexia, OCD and depression after experiencing suicidal thoughts. She was sectioned, and made subject to deprivation of liberty safeguarding.

At the time, Helen says, she didn’t know what ‘personality disorder’ [PD] meant – but she quickly began to feel the stigma that comes with this diagnosis.

“The words themselves are bad enough. ‘Personality-disordered’, ‘borderline’, ‘emotionally unstable’: all of those words are loaded, stigmatising terms,” she says. “I noticed more and more the way I was treated, and the way people with the same label were treated compared to other people differently diagnosed.

“There were times where I was explicitly told: ‘You're not mentally ill, you’ve just got a personality disorder’, or, ‘You're doing this for attention’, or, ‘PD patients are really difficult’, or, ‘I don't like working with them’. To a child, that is particularly heinous.”

A decade later, the practice of diagnosing under-18s with a personality disorder persists, despite a widespread campaign to end the “harmful” practice. According to a new freedom of information [FOI] request submitted by The Lead, 18 NHS trusts in England diagnosed under-18s with a PD in 2023.

One of the most prolific trusts according to our FOI was South London and Maudsley. The trust reported diagnosing 25 patients under 18 with ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ – which is another name for borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Perhaps just as concerning were the nine NHS trusts who responded saying they did not know whether or not they had used this diagnosis for under-18s.

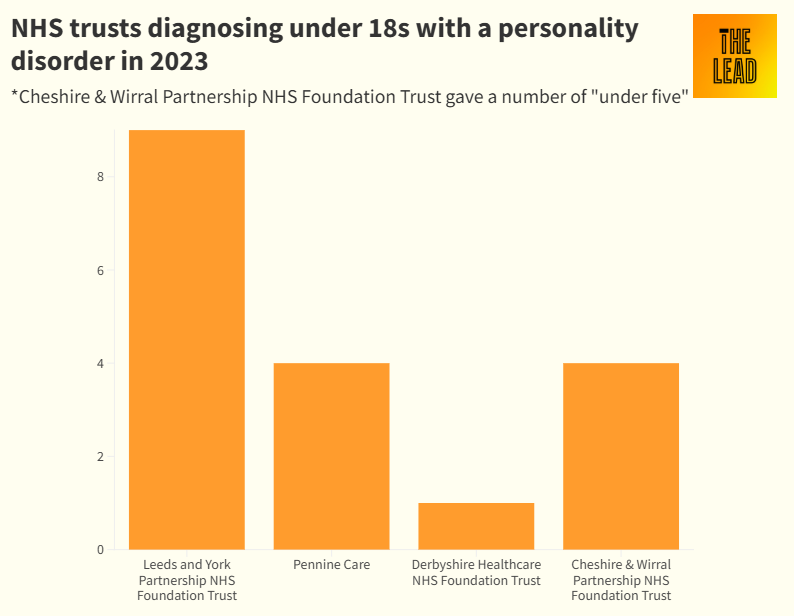

In the North East and North West:

Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust diagnosed nine patients under 18 with personality disorder in 2023.

Pennine Care reported making four new diagnoses of personality disorders in patients under 18 in 2023.

Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust diagnosed one patient under 18 with a personality disorder in 2023.

Cheshire & Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust also made new diagnoses in 2023; it said it had diagnosed ‘under five’ but didn’t give the exact number because of concerns about identifying individuals involved.

Last year, hundreds of professionals signed an open letter written by Sir Norman Lamb, a former health minister, and an expert by experience, Sue Sibbald. Campaigners argued that diagnosing personality disorder in under-18s is “abhorrent, unethical, harmful”. Signatories included psychologists and psychiatrists, as well as nurses, therapists, and occupational health practitioners.

In 2018, these two authors co-chaired a consensus statement on personality disorders. The Royal Colleges for Nursing and General Practice, and the British Psychological Society (the professional body for psychologists) proposed to “abandon the term ‘personality disorder’ entirely”. But seven years on, the term is still in use.

Diagnosis by another name

Six trusts reported that they did not diagnose any under 18s with personality disorder – which, on the face of it, appears to be a great result for campaigners.

The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, for example, reported that they “do not generally” diagnose personality disorder in under 18s and prefer to provide a service “based on need rather than a diagnosis”.

But patients and experts have raised concerns that there may be other ways children and young people are labelled beyond being officially diagnosed. Like Helen, a child or young person may be given the label of ‘emerging’ personality disorder – which is an umbrella term used for children rather than an official diagnosis.

This seems to be the case at the Dorset Health University NHS Foundation Trust, which said: “Clinicians may have a working diagnosis of emerging EUPD, but the emphasis is on ‘emerging’ and we would not diagnose in young people under the age of 18.”

But there’s a problem with this label lingering even after a patient grows up. Helen recalls that when she transitioned into adult services, her ‘emerging’ PD diagnosis was carried across without question.

“My psychiatrist in adult services gave me a PD diagnosis the first time I met her,” she says. “I asked, ‘What is my diagnosis now?’ And she said, ‘It's obviously BPD’. She had never met me before, and she never carried out an assessment or looked at the criteria with me. Because I had this ‘emerging PD’ label on my records from CAMHS, it seems like it automatically transferred across to adult services as a PD diagnosis.

“An ‘emerging’ label is considered a PD, as far as I'm concerned.”

Helen believes what happened to her is commonplace.

“Of all the people I know who had an ‘emerging’ label, myself included, as soon as we turned 18 it just went on to the paperwork as PD,” she says. “So what is the point of there being an ‘emerging’ label? If the treatment or care doesn't prevent ‘emerging’ PD from becoming a full personality disorder, then it’s only there because it's distasteful to diagnose personality disorder under 18.”

A harmful label

The NICE best practice guidance states personality disorder assessments should not be completed until 25 years of age.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Lead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.