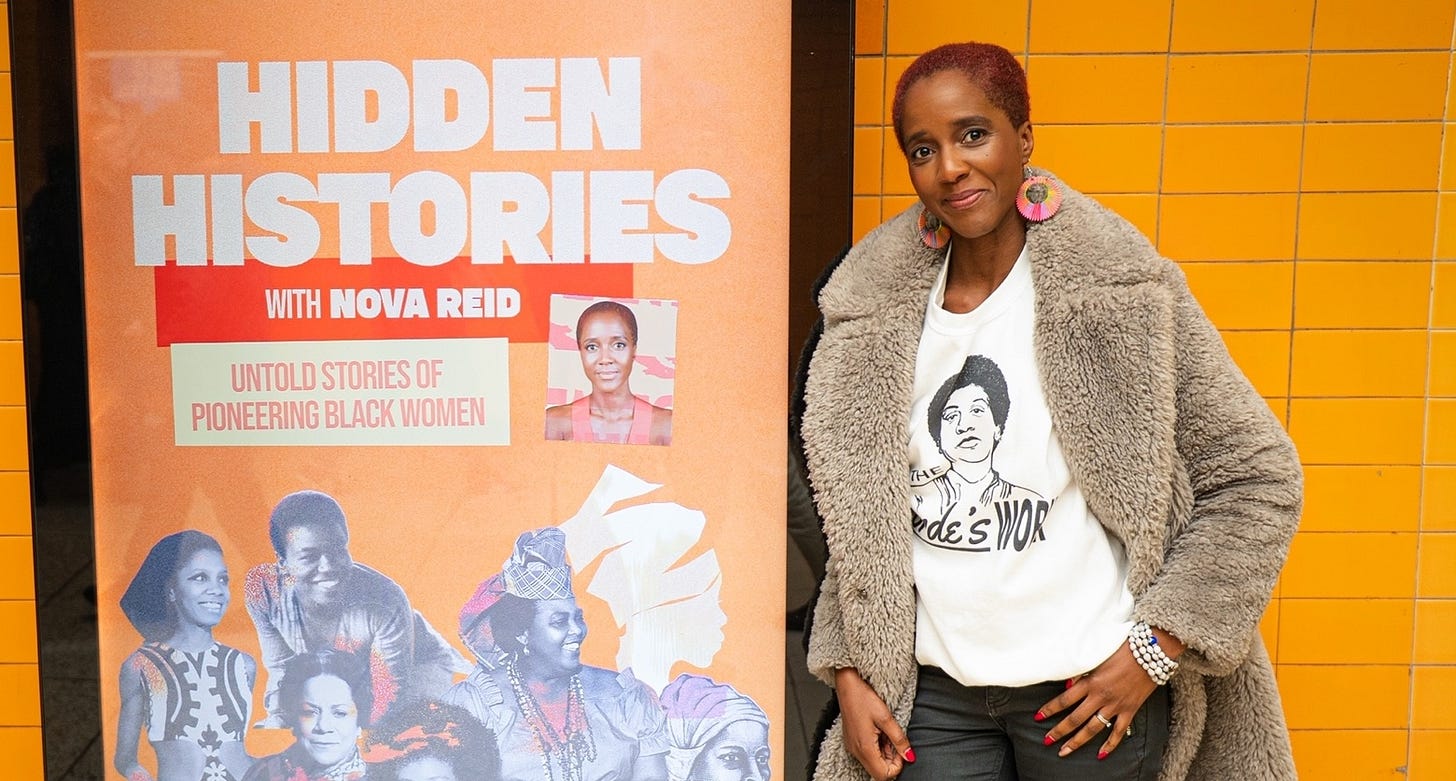

Hidden Histories: These are the Black women we should learn about in school

Black women’s stories are often erased or deliberately hidden, Nova Reid's new podcast urges you to get to know the pioneering Caribbean women who have shaped our culture.

From London to Leeds to Jamaica, in her new podcast Hidden Histories with Nova Reid, Reid introduces listeners to the worlds of extraordinary Black women whose stories have been buried for too long.

Delving into the lives of pioneers, journalists, and…