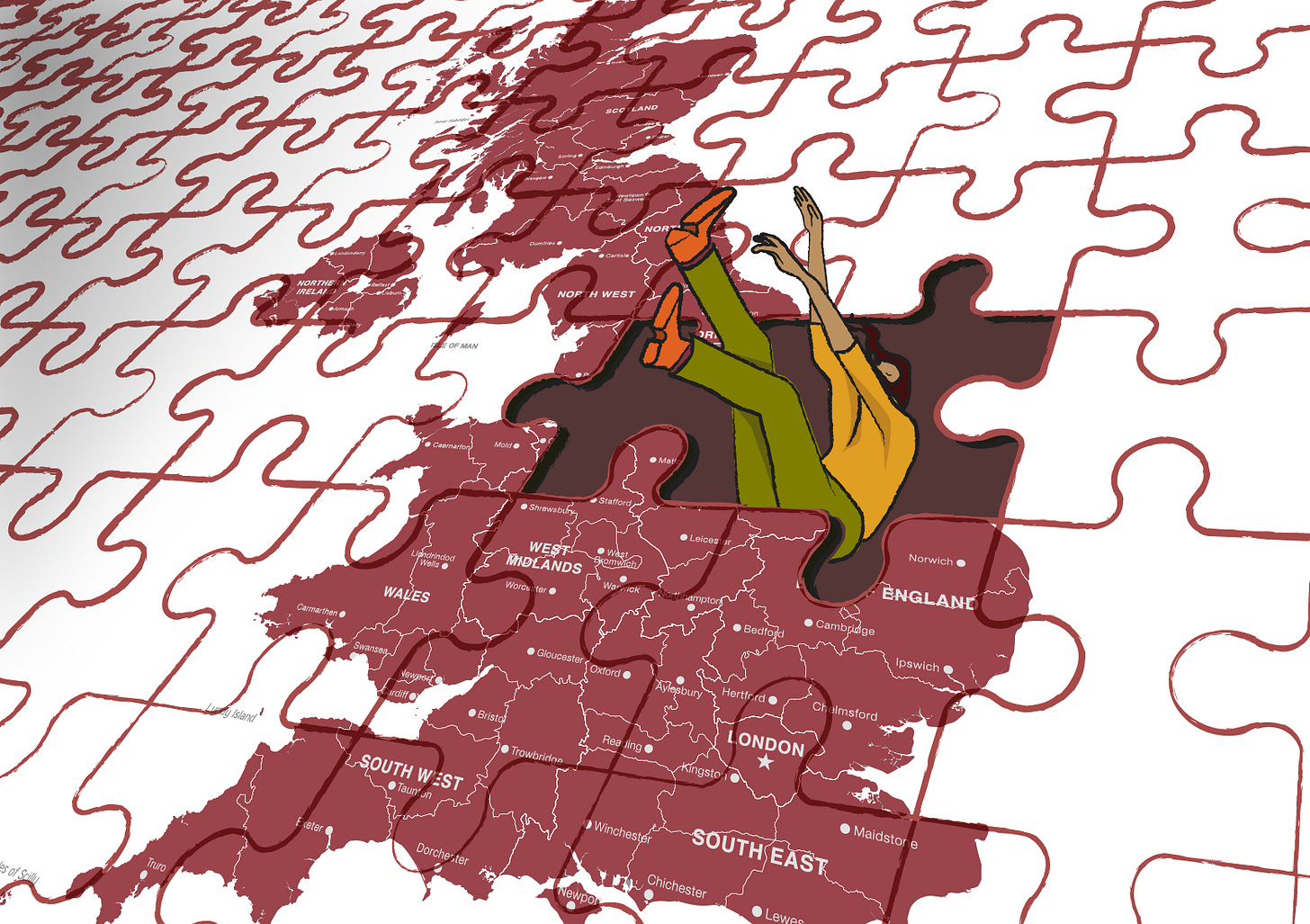

Inaccessibility, inequality and poverty: What's really disabling the nation?

As the government prepares sweeping changes to PIP and disabled benefits, we ask what's behind the rise in disability numbers – and what needs to happen now.

Rates of disability and chronic illness in the UK have increased steadily for years, inspiring successive governments to slash essential benefits from one of society’s most vulnerable groups.

The numbers are likely to continue rising: a 2023 Health Foundation report projected a 37 per cent increase in people living with a ‘major illness’ by 2040; the majority will be over 70, with a 4 per cent rise predicted among the working age population.

The disabled community is over 16.1 million strong in the UK – translating to approximately 1 in 4 people – and soars above 1.3 billion globally, yet, too often, accusations of ‘laziness’ and an ‘over-diagnosis’ of mental health conditions are wielded to dismiss this diverse population’s needs.

However, the real culprits contributing to the disabling of the nation are far more complicated than politicians’ favourite buzzwords. The UK has steadily contributed to the rising rates through a series of mistakes, the most recent of which was ignoring the consequences of the COVID pandemic – argued by some as the biggest mass disabling event in history.

When Sian Fox-Gaven, 33, contracted Coronavirus in December 2021, she thought the effects would be temporary. However, within a few months, Sian joined one of approximately 2 million people living with Long Covid in the UK, a disability still devastating lives five years after the world closed down.

“I thought, I’ll have the Christmas holidays to recover and I’ll be fine and ready to go in January when we return – obviously, that didn’t happen,” she says.

Sian had just been promoted to deputy headteacher when Long Covid came for her energy, strength, and mental health. The dedicated teacher had to take nearly a year off work on paid leave, but when she tried a phased return, she couldn’t manage it and had to give up work entirely.

“I didn’t feel I was the same person anymore, I was disabled,” she says. “But I didn’t see it that way for the first year because I thought, ‘it’s going to clear up and I’m going to go back to work.’”

Sian now relies on mobility aids to conserve energy when leaving the house. Though grateful for the assistance they give her, she has realised the world around her is no longer built with her in mind.

“Going out in a mobility scooter and a wheelchair you realise the world is so ableist and inaccessible. I find leaving the house really hard. Is my scooter even going to manage on that cobbled street? Or are there going to be dips in the pavement?” she says.

Despite everything, Sian sees herself as lucky in some ways because she lives near a Long Covid treatment centre in Bristol that has just received a further six years' funding.

New research shows that the number of NHS clinics for Long Covid in England has more than halved since its peak of 120 in 2022. There are now just 46 clinics catering for patients all over the country.

Despite patients’ ongoing need for support, many are left floundering, becoming increasingly disabled by their condition in the absence of robust medical care. It’s not just people with Long Covid struggling to cope with the disabling effects of the pandemic, though.

“It’s hard to say what exact impact the pandemic had on the number of people recorded as disabled by the government; however, we know that many of the people we support at Sense were further disabled by the societal impacts of the pandemic,” says Georgina Smerald, policy research manager for Sense.

“For example, over a third of disabled people with complex needs, 36 per cent, did not get the social care support they needed during the pandemic, creating significant barriers to them living a healthy, independent life.”

Beyond the pandemic

Rates of disability and long-term illness have consistently increased for over a decade, rising from 19 per cent in 2012/13 to 24 per cent in 2022/23.

Contributing factors are myriad: spiralling poverty levels, failing preventative healthcare, and lacking social care support, to name just a few.

The combination of the postcode lottery in healthcare and rising poverty levels plays a central role in increasing rates of disability, reflected in The Health Foundation’s research. People in the 10 per cent most deprived areas are expected to be diagnosed with major illness a decade earlier than people living in the 10 per cent least deprived areas of the UK.

Leeds-based Jennifer Han believes that growing up in poverty had a profound impact on the severity of her rheumatoid arthritis, which was diagnosed years too late for early intervention treatments.

“Living in poverty shaped my mindset about health until I reached adulthood,” says the HR expert.

“Our family didn't talk about preventive healthcare because we couldn't afford it; my family needed to pay for necessities first, so they let minor health problems become unmanageable until they needed immediate medical attention.”

Despite struggling with joint pain throughout childhood, Jennifer wasn’t diagnosed until her mid-20s, by which time the doctors said the condition had caused irreversible damage. Although the family were never careless, they avoided seeking medical help unless the issue was visible or life-threatening because it wasn’t always possible to access healthcare without compromising their income.

“Taking time off work for a doctor's appointment resulted in lost wages, which disrupted the weekly budget plan,” she explains. “The cost of prescriptions remained a barrier to complete treatment even in cases where appointments were secured.”

“Allowing disabled people to remain in poverty keeps them trapped in a cycle of ill-health, unable to access work or adequate social support. In short, poverty disables.”

With 1 in 5 people in the UK living in poverty, Jennifer’s experience is being replicated generation after generation, disabling people by depriving them of easy access to healthcare and the necessary knowledge to prevent chronic illnesses from becoming more severe.

Aside from poverty contributing to rates of disability, the disabled community is more likely to live in poverty, meaning the impact of their conditions is exacerbated by a lack of support or a stable income.

The UK Poverty Report found that the additional costs associated with disability and ill-health – something Scope estimates to be around £975 extra per month – contribute significantly to 31 per cent of disabled people living in poverty, 12 per cent higher than the rate for non-disabled people.

People with layered marginalised identities, including people of colour and LGBTQ+ people, are also likely to face higher rates of poverty. Allowing disabled people to remain in poverty keeps them trapped in a cycle of ill-health, unable to access work or adequate social support. In short, poverty disables.