Schools are still hiding the violent truth of the British Empire

Historian Paula Akpan on what's missing from the curriculum. Plus: The Black women of history erased from the record books + an exclusive extract of Akpan's groundbreaking debut book.

Speak to many in the UK, particularly Black and brown folks, about their formative history education, and you will encounter some version of – “we never learned about XYZ at school” – especially when it comes to the role Britain played on the global stage, i.e. empire and colonialism.

As a historian, I hear it so regularly that it has become a cliché. But most clichés are wrapped around a kernel of truth, and the truth here is that the British education system obfuscates the violence necessary for a British empire to exist.

The UK government’s national history curriculum from Key Stages 1-3 outlines aims like ensuring all pupils “know and understand… how people’s lives have shaped this nation and how Britain has influenced and been influenced by the wider world”, develop a “historically grounded understanding of abstract terms such as ‘empire’ [and] ‘civilisation’”, and “discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations of the past have been constructed.”

While KS1 sits as an introduction to vocabulary and chronology, the curation of topics (with non-statutory examples) at KS2 and KS3 is telling.

“While great attention was paid to the horrors that emerged from Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow South, nowhere did I learn that the British Empire colonised about one quarter of the world’s landmass.”

A student between the ages of 7-11 will learn about the advent of the Roman Empire, resistance to Caesar’s overtures through figures like the flame-haired Boudica and the ‘Romanisation’ of Britain, which shaped technologies, culture and belief, such as early Christianity. Here, pupils are offered a peek at the demands and violences of imperialism, but what’s missing is the connecting dots – British complicity in these same behaviours.

Other notable areas of study include achievements of early civilisations, where educators offer an in-depth appraisal of one of the Ancient Sumer, Indus Valley, Ancient Egypt and the Shang Dynasty civilisations, as well as the study of a “non-European society that provides contrasts with British history” such as Bénin (900-1300 CE). Whatever form these ‘contrasts’ take seems open to interpretation.

As students make the jump to secondary school life, mandatory humongous rucksacks in tow, their history education takes on a more steely form.

Now expected to compare, contrast and analyse evidence, by KS3, young people are expected to be able to “discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations of the past have been constructed.” Here, they’re introduced to the socio-political undergirding of history work, how attitudes that emerged from the Enlightenment period shaped the Industrial Revolution, political theatre and British imperialism. However, in the topic area that pertains to the British empire, spanning 1745-1901, only two examples (again, non-statutory) would likely go anywhere close to troubling the myths of Britannia: “Britain’s transatlantic slave trade: its effects and its eventual abolition”, and “Ireland and Home Rule”.

From my own recollection, KS3, GCSEs and even A-Levels went nowhere close. While great attention was paid to the horrors that emerged from Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow South, nowhere did I learn that the British Empire colonised about one quarter of the world’s landmass, nor that, after a survey of 200 countries, it was discovered that Britain had established some kind of military presence in all but 22 of them.

Nowhere did I learn that Britain only closed its doors on enslavement because it was no longer profitable, nor that emancipation for enslaved people didn’t begin until 1838, not in 1833 in line with the Act of Abolition of Slavery – during those five years, enslaved people continued to work for British slave-owners who were compensated for their loss of abducted and exploited Africans.

And I certainly didn’t learn about how Britain treated indigenous African societies and their rulers, particularly those, like Ranavalona I of Imerina (present-day Madagascar). An early 19th century figure who resisted Western colonial interference, Ranavalona’s realm was subjected to attacks and raids from British and French forces, retaliating to the Malagasy ruler’s refusal to enter into friendly relations. This is just one ruler from one of the many indigenous societies forced to live under British occupation, deemed incapable of ruling themselves or making use of their coveted resources.

Given the aims stated in the curriculum, the disappearances of the true role of the world’s most violently successful empire is all the more audacious. And, added to the appraisal of Britain’s ‘Romanisation’, the careful sidestepping of our own role in colonisation becomes all the more galling. The frameworks and vocabulary are there and our institutions know how to use it, but only when it suits.

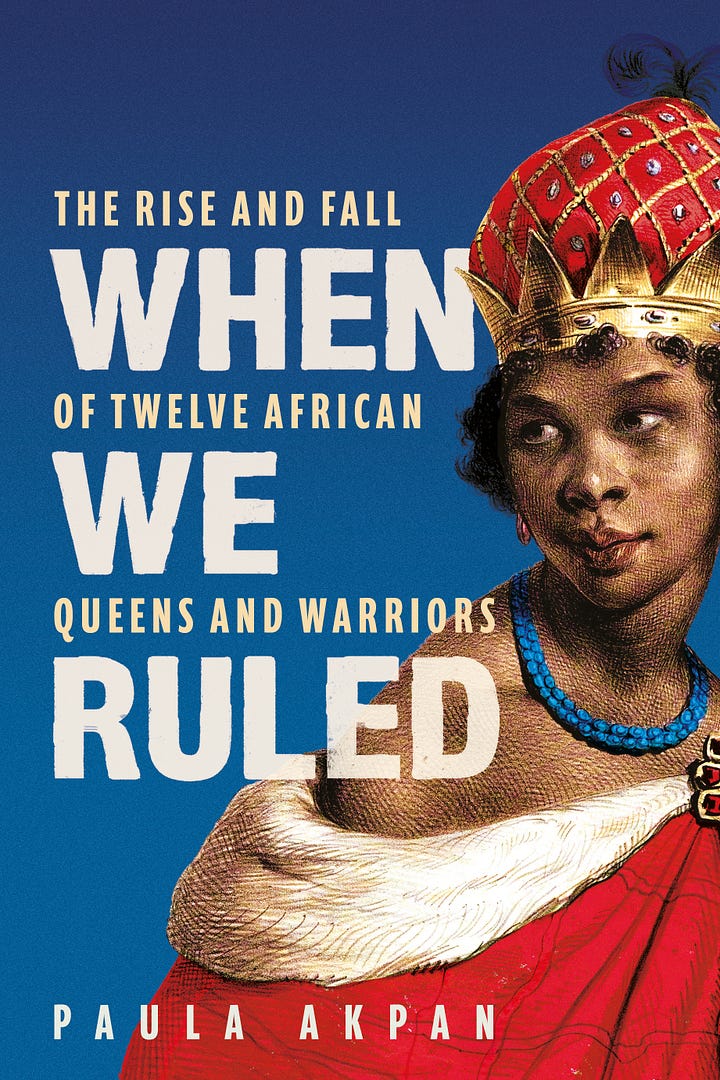

About the author: Paula Akpan (she/her) is a Black British historian and writer with credits in Vogue, Teen Vogue, The Independent, Stylist, VICE, i-D, Bustle, Time Out London and more. When We Ruled is her debut book.

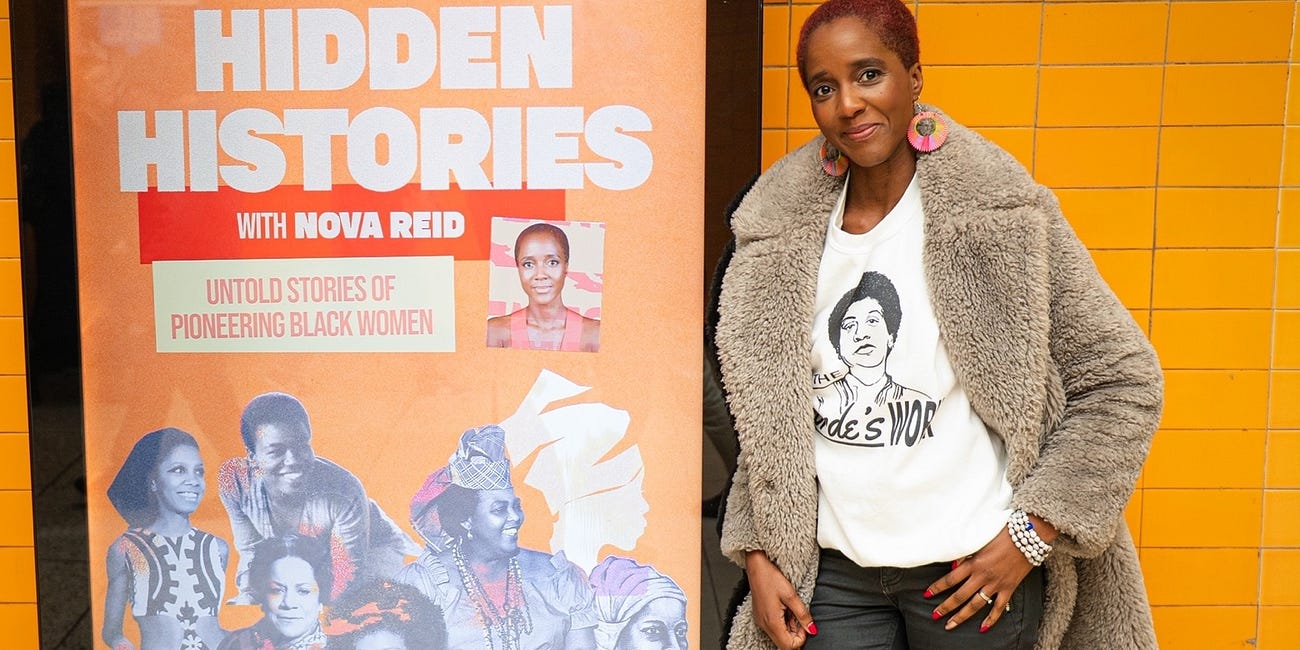

Black women’s stories are often erased or deliberately hidden, Nova Reid's new podcast urges you to get to know the pioneering Caribbean women who have shaped our culture.

Hidden Histories: These are the Black women we should learn about in school

From London to Leeds to Jamaica, in her new podcast Hidden Histories, Nova Reid introduces listeners to the worlds of extraordinary Black women whose stories have been buried for too long.

Paid subscriber feature

Today we are offering an additional feature only available for paid subscribers. Consider subscribing to read an exclusive extract from Paula Akpan’s groundbreaking debut book When We Ruled:

When We Ruled: "History is written by the hungry"

History is written by the victors, a white man said. It continues to be taught by the victors. From formative school years through university, history has always been presented as concrete, whole, lacking any veneer. We learnt about the Irish Potato Fam…

Thanks for reading this special edition of The Lead. You can read lots of our other work on education and inequality, from Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff writing about Black girls facing violence in schools, to Hannah Fern on the “lost generation” of home-schooled kids, to our senior editor Natalie Morris reporting on the scandal of Windrush children pushed out of mainstream schools by a racist education policy.

Consider becoming a paid subscriber to access additional, exclusive, content and support our mission to bring your insights and perspectives beyond the mainstream headlines on people, policy and place.

Natalie, Luke, Zoe, Ed, Ella and The Lead team

As an Irish person growing up in the UK, the curriculum taught me that Oliver Cromwell was something of a heroic figure. It was only after leaving school that I learnt what a monster he was. How he coralled and then burned women and children in Ireland. He was, in truth, hated and vilified both in Ireland and in his own country. In todays world he would be sectioned and put into a soft walled room. The British education system, in regards its history curriculum, is little more than propaganda and downright mistruths. Perhaps this goes some way to explain how BBC journalists and their ilk can so easily and shamefully vomit such biased views of current global events. Netanyahu, for instance, is portrayed as a political leader defending his people. In truth he is the Cromwell of our times. A psychopath intent on self preservation and happy to burn women and children to keep the distorted power he possesses. A power emboldened by the shameful stance taken by UK and western media. Homeschool your kids if you prefer them not to be shovel fed propaganda and lies.