The North is watching and waiting for Rachel Reeves to act on child poverty

Former Editor of the Big Issue North, Kevin Gopal, looks at how families in the North of England are in dire need of help - and why the child poverty strategy must right many years of wrongs

Even with less than two weeks before the expected launch of the child poverty strategy, there is a need to maintain pressure on the government if it’s to improve the lives of nearly a million poor young people in the North, an expert has warned.

The abolition of the cruel two-child benefit cap has been widely trailed as the cornerstone of the child poverty strategy, promised in Labour’s manifesto, delayed in spring and predicted to coincide with Rachel Reeves’ Budget on 26 Nov. But this week’s flip-flopping on income tax shows nothing is an entirely done deal.

Removing the cap would be the quickest and most effective way of lifting children in the North out of poverty, agrees Rachel Walters, manager of the End Child Poverty Coalition.

But she warns it must be removed in full, and not replaced with a three or four child cap or merely a tapering increase in benefits for larger families. And although ending the cap is a necessary part of the strategy, the End Child Poverty Coalition says it is not sufficient.

Among a series of further tests, it says the government should also commit to halving child poverty in 10 years, and to further funding for social security and public services.

The strategy might be completed from a civil service point of view, says Walters, but even now the political decisions are still to be made – meaning an opportunity and a need for continued lobbying. “It’s still very much to play for.”

The numbers on child poverty in the North

Child poverty is at an all-time high in the UK according to official statistics, with 4.45 million children living in households with an income below 60 per cent of the median, after housing costs, in the year to April 2024. That equates to 31 per cent of children nationally, a figure projected to rise by the end of this Parliament without action.

Child poverty hits particularly hard in the North. A report for the All Party Parliamentary Group Child of the North put the number of children living in poverty in the North during the pandemic at 900,000, which will have risen since.

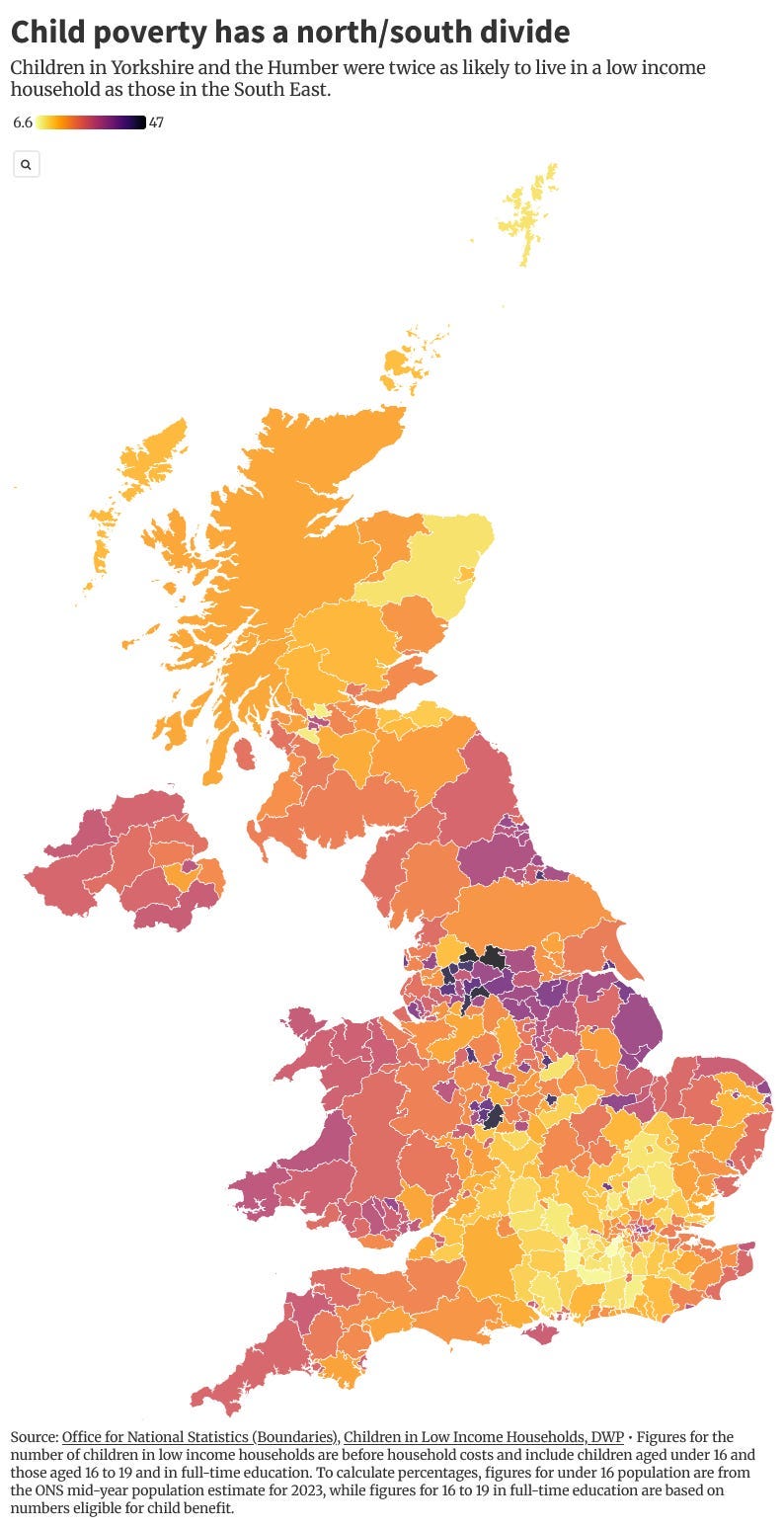

Analysis of official data by Loughborough University shows that the West Midlands and London are the regions with the worst figures, with 36 and 35 per cent rates of child poverty. But the North West (35 per cent), Yorkshire and Humber (32 per cent) and the North East (31 per cent) are next worst.

Constituency and local authority figures show the problem in the North to be even worse.

The constituency with the highest level of child poverty is Birmingham Ladywood, at 62 per cent. But Dewsbury and Batley (58 per cent), Bradford West (57 per cent), Bradford East (55 per cent), Leeds South (52 per cent), Middlesbrough and Thornaby East (52 per cent), Manchester Rusholme (51 per cent) and Liverpool Riverside (50 per cent) are among the few constituencies in the country where a half or more children are in poverty.

Explore child poverty by place below in our research by data journalist Claire Miller and view the map and read more about her exclusive deep dive into the numbers behind child poverty.

By local authority, according to Health Foundation analysis, Pendle, Bradford, Oldham, Birmingham, Blackburn with Darwen and Manchester had the worst child poverty in the country.

The hidden true scale of child poverty

Sophie, from Newcastle, believes this northern picture isn’t fully understood by policymakers and the media. She grew up in poverty with her three siblings in a single-parent household and would regularly skip breakfast while others ate.

“I watched my mam do it. I was like, this is what women do – I’m going to do it now.”

She shared a bedroom with two sisters in a house where poor conditions are only now being addressed after the family moved in 14 years ago. That affected her ability to study.

“When you’re younger and you’re in it it feels normal. Where I’m from everyone was in the same boat. It’s not just my mam who was in poverty – it’s generations before that. It felt like something that was going to be me forever. It feels like you’re trapped there.”

Sophie is now a student in Leeds and acts as a youth ambassador for the End Child Poverty Coalition.

“I’m very open about the fact I grew up quite poor. But the North, especially the North East, gets left out of conversations. It’s very easy to look at poverty as a straightforward thing but I do think it differs from place to place.”

For her, ending the two-child cap should be a given. “It’s not like we’ll have to wait 20 years to see a difference. It’s something that will happen instantly. That has to be the main priority.”

Nor have the far-reaching consequences of child poverty been fully understood, according to David Taylor-Robinson, professor of public health and policy at Liverpool University and academic director at Health Equity North.

With colleagues, he has built up an evidence base showing the harm of child poverty on infant mortality, children’s life expectancy, child obesity, mental health problems, educational attainment and more.

“It’s a really grim picture when it comes to children’s health and it particularly affects the North,” he says. “Places like Liverpool, Manchester, the big urban centres are all at the sharp end of all of these health inequalities.

“It’s pretty clear what’s caused it – we’ve built this evidence base over a long period of time. It’s caused by austerity measures. We started to see these trends around 2011-12.”

Statistics on children in care are an example of the strength of that evidence base, which Taylor-Robinson says has caught the eye of Bridget Phillipson and Keir Starmer and gained some traction. A Lancet paper showed that most children went into care because of neglect, and that was linked to poverty. Ballooning care budgets are the main reason local authorities are going bust.

“It’s a horrible example of the doom loop – child poverty causing adverse conditions for families. At the sharp end of that some children end up in the care system. That’s hugely costly for all of our systems. Then local government can’t afford to invest in prevention,” he says, adding that the same is true of mental health.

“Pressure on public services caused by the consequences of child poverty are hard to deny but I don’t think people quite get that.”

Voluntary sector picking up the pieces

Local authorities and charities, neither awash with money, are trying to pick up the child poverty pieces.

Caritas Salford is a charity that runs 14 grassroots anti-poverty services across Greater Manchester and Lancashire, including a fund for families in crisis, and young parents’ accommodation in Blackburn.

It has sourced furniture and small grants for a single parent of six whose father no longer contributes to their upkeep following relationship breakdown. She was living in bare rooms with no curtains or wardrobes, and two children lacked proper beds. The washing machine was broken, and the family had no way to dry clothes.

In another family it worked with, the youngest child was hospitalised and paying for public transport to and from the hospital meant they couldn’t afford to pay for the children’s school meals or provide sufficient food at home. The charity helped with grocery vouchers.

In a recent survey of Catholic school leaders, Caritas Salford found a “significant increase” in child poverty on its patch in Greater Manchester and parts of Lancashire. Nearby Lancaster has a relatively low 23 per cent in child poverty. But the rate has grown to its highest figure since 2013-14 and can reach 45-60 per cent in wards such as Westgate, Skerton East and Skerton West, says Green Party city and county councillor Gina Dowding – “astonishingly hidden and worrying”.

She praises local initiatives such as Citizens Advice North Lancashire working with Morecambe Bay Foodbank to provide tailored support in schools for young people facing food poverty. And as a member of the Progressive Lancashire opposition group to Reform on Lancashire County Council, Dowding backed a successful motion to set up a commission examining the impact of poverty and inequality on educational outcomes. But ultimately, says Dowding, child poverty is driven by national issues.

“The quickest win that would bring hundreds of thousands out of child poverty would be to scrap the two-child benefit cap and we’ve been campaigning for this since it was introduced. I find it astounding that Labour haven’t done that yet. “Let’s just hope they are finally going to see sense – but who knows? It’s important that everyone keeps the pressure on. The stakes are so high in terms of the lasting impact on a whole generation of children.”

The Greens’ general election manifesto pledged to increase Universal Credit and legacy benefits by £40 a week so that “people can live with dignity and not be reliant on food banks”, says Dowding. “But in the long term we’d like to see a different approach with the welfare system – a universal citizen’s income scheme so everyone has that security through life.”

A council not waiting for government action

In Preston child poverty actually dipped between 2017 and 2021 before climbing again – but even then at a lesser rate than surrounding areas of Lancashire.

Preston City Council leader Matthew Brown puts this down to the so-called Preston Model of community wealth building, which includes the promotion of a real living wage, maximising social and affordable house building, and prioritising local suppliers for procurement.

It’s also supported food hubs, benefits advice and home insulation for the poorest, even as its funding has been cut by a third.

“We feel we’re bucking the trend because of these local measures,” says Brown. “However it’s still devastating that child poverty has risen.

“Fourteen years of Tory and Lib Dem austerity has really battered communities like ours.

“The figures across Lancashire have been worse than many other areas in terms of child poverty, which is devastating for working class communities like this. We’ve tried to fight back as strongly as we can.”

Now Preston City Council is launching a new series of measures to alleviate poverty, spending £800,000 on targeted and universal measures including free swimming for children and older people, a one-off Christmas payment of up to £400 for families affected by the benefit cap and grants for grassroots initiatives to tackle poverty.

“As a Labour council that’s quite well off we do want to redistribute wealth to the less well off,” says Brown. “People just do not have enough money in their pockets in this community. For me it’s thinking about those kids – they deserve a bit of a boost.”

Brown says the government has been listening and he would welcome the end of the two-child cap. The minimum wage rise is “brilliant” but he’d like to see it a lot higher.

“But we also need a radical redistribution of wealth and power in this country. The poor’s voice is often not listened to. That is a real problem.”

The government has boxed itself in with its arbitrary fiscal rules and by fostering talk of a welfare bill that’s out of control when in fact it’s been relatively stable as a proportion of GDP for a number of years.

Walters says sometimes Labour politicians think they’ll lift child poverty just by being the party in power – “but you have to commit funding to do that”.

The child poverty strategy will be the test of that.■

About the author: Kevin Gopal is a Manchester-based journalist who has returned to freelancing after editing Big Issue North from 2007 until its closure in 2023.

Here at The Lead, we’re campaigning to end child poverty. We have already reported on the crisis as a failure of the state, and the under-reported racial inequalities lying at the heart of child poverty. We’ve also gone deep into what’s happening in the Northern towns and regions we report on with our award-winning Lead North titles, examining what’s happening with child poverty in Blackpool (a town regularly shown as being amongst the most deprived in the country) and also the impact it is having on Lancashire where areas considered as ‘affluent’ are showing stark rises in the number of children in poverty.

If this is an issue you care about, share this article to raise awareness and help more people discover our journalism.

Subscribe to The Lead today and get a 30% discount on annual membership – only available until the end of November.

They’ll be waiting a long time, as the Labour party no longer gives a shit about the poor.

I fully agree with your ‘campaign’ on child poverty and the removal of the 2 child limit.

However you have published some ‘wild’ claims from Matthew Brown that have no basis in evidence or fact. This is not decent journalism, it’s just finding someone who agrees with your original premise and then using that to justify your narrative.

Perhaps a little more attention to detail and further questioning might gives us all better evidence.

Matthew Brown has a job outside of the Council which pays him to promote Community Wealth Building. A vested interest? You should have asked shouldn’t you?